Hallucination Engine Revisited: Psycho-Dynamic Obsolescence of General Motors

I am a child of General Motors — an ex-auto junkie United

Auto Worker raised in dealerships and auto plants. I am peak oil,

the auto-sprawl,

carbon dioxide, speed and redundant mobilty.

This

is the intervention. This

is the intervention.

Today,

I shop on the showroom floor of illusions. Amidst Ford‘s

chest-thumping “we will survive without a bailout” proclamation,

Chevy’s greenwashed prediction that their extended-range

electric Volt (another candidate to overload the grid) will cure

post-Chapter

11 pain, and taxpayers’ frustrated cries from adjusting

to the dubious understanding that they have suddenly become stockholders

with no voting rights in the sputtering American auto industry,

my

Zeitgeist – “What’s good for General Motors

is good for America,” went bankrupt. Hummer rolled over;

Saturn eclipsed; Pontiac and Oldsmobile phased out. While the

post-bankruptcy

GM announces it will focus on "developing vehicles that can excite

buyers," all I feel is the wisdom of dead junkies, that but for

the grace of God…, and the dynamic obsolescence of hyper-mobility.

—

I

was a kid at a red light between the bucket seats of a 1958

hot-off-the-showroom-floor, two-tone Corvette convertible, top

down under an surreal March morning

sky, a Chevrolet jingle on the radio with a chorus singing "It's

all new all over again." When the light turned green,

the melody accelerated through my skin and evanesced into

the hills

above Sunset

Boulevard. I was hubcap-eyed hypnotized.

At

the wheel, wearing his favorite Don Loper shirt, Dad — a

parts department employee at Martin Pollard Chevrolet — smiled

sweet and satisfied like Jack Lemmon at 29. Next to him, Mom

smiled back in Shimmering Rose lipstick and butterfly dark glasses,

her

Vera scarf straight in the wind. Cruising west on the Sunset

Strip, we

were enshrined in the 'Vette — a Panama Yellow and Snowcrest

White barking GM spider dripping chrome. At

the wheel, wearing his favorite Don Loper shirt, Dad — a

parts department employee at Martin Pollard Chevrolet — smiled

sweet and satisfied like Jack Lemmon at 29. Next to him, Mom

smiled back in Shimmering Rose lipstick and butterfly dark glasses,

her

Vera scarf straight in the wind. Cruising west on the Sunset

Strip, we

were enshrined in the 'Vette — a Panama Yellow and Snowcrest

White barking GM spider dripping chrome.

My

eyes locked on the cloud-and-rooftop horizon above the dashboard.

Sparkplug bolts

of electricity hard-wired my brain. After a

fuel-injected hit of 20th-century freedom and mobility, I

was never the same

all over again.

"Let's

make this thing work," said Dad stepping on the gas.

The

engine om submerged me in a V-8 adrenaline bath. Lost in a 290-horsepowered

paradise-to-the-bone, I was 8-years

old and

burning-down-the-house

addicted to cars.

Before GM, we were clean. A few city blocks supplied all

the life we needed. We walked to work, to school, to shop

for

groceries. The church. The dry cleaners. The drugstore.

The bank. Our close

friends.

Get in a car to visit them? Never. Cars were meant for

a trip or a special occasion — not for a mundane

commute or errand. Let me explain in market terms for

investors in the new GM. Back in the

day, stocks were based on earnings, not derivatives; executive

salaries had something to do with portfolio performance;

you had to have verifiable

income to qualify for a loan; people had some idea of

to whom they owed money and sense of where that money

might come from. Get it?

But

we became addicts. We dressed for cars, schedule for

cars, wished for cars, cursed for cars and lusted for

cars. Our

leisure time,

speech, manners (or lack thereof), where we did business

and pleasure was

auto-dependent. We loved and hated cars, gave them names,

sang about them, insured their bodies, rubbed them until

they shined.

Deluded

into thinking that the outward rush of motorcar markets

could expand infinitely, we came to think of our planet

in the same

way — an

inflating globe growing without limits.

At

first it was 10 miles…then 50…100…200 miles

a day. Soon we couldn’t even eat without a car — all

of our behavior deformed in a Möbius strip cloverleaf

head-on crash. And now, GM is back from DOA. If that’s

a good sign, fuck me.

—

On

my way to work this morning, out-of-control Japanese taillights

flare and spin by. I've almost been

hit by a rice rocket trying

to avoid a squirrel. My Camaro is okay, but I'm

a wreck. I take a deep

breath.

"Try

to relax," I say. "Blend into traffic. Sink into your

leather seat. Get lost in the drone of the engine.

Flatten the wayward squirrel."

But

when I arrive at my office, I'm shaking — my

malignant inclination driving me downhill, shifting me between loving cars

and desperately

needing cars. Jesus Christ in a GTO, I need help.

It's time to call a doctor.

If

anyone can make me feel good about my automotive Jones, its Dr.

Kenneth Green, the ex-Director

of Environmental Studies at the Reason

Public Policy Institute, now-Resident Scholar

at the American

Enterprise Institute. He’s an old school

invisible-hand-of-the-marketplace libertarian.

Surely, he can talk me back up.

"There's

no validity to the argument that we are somehow addicted to cars," Green

says. "When someone approaches

me from your viewpoint, I just say two words:

'Conestoga wagon.' The truth is,

we've wanted greater mobility since the covered

wagon."

Cool.

I keep quiet and listen. Economics is the driving force behind

the preponderance

of

cars,

according

to Green. We are,

essentially,

going places either to get money or spend

it. A wagon. A bicycle. A horse. An Acura. To a

good American

with

his

head on straight,

they're all simply economic conveyances. I

sense that this might be useful

information in my new role as a multi-tasking

taxpayer / stockholder in the new GM. Cool.

I keep quiet and listen. Economics is the driving force behind

the preponderance

of

cars,

according

to Green. We are,

essentially,

going places either to get money or spend

it. A wagon. A bicycle. A horse. An Acura. To a

good American

with

his

head on straight,

they're all simply economic conveyances. I

sense that this might be useful

information in my new role as a multi-tasking

taxpayer / stockholder in the new GM.

Outside

my second-floor window, a

Harley Davidson rumbles past, its antisocial posture splitting

the lanes

of the stagnant

citizenry. I

reel in a learned

neuro-synaptic response. A dopamine surge

brings me to my senses. What a

load of crap. A car is so much more than

a vehicle. It’s part of our

identity. A 57 Chevy is not a conestoga

wagon. It’s an obsession.

"We

have a demand for mobility that is almost insatiable," Green

informs me. "There's no limit to

how far people will want to spread out."

I'm

listening, but an engine starts humming

in my head. The room undulates. The

ceiling peels

back,

and a dark

universe emerges

above me. I rise

into it, enveloped in a future where

only one person inhabits each planet: A deep-space

version

of an

upscale gated

community — Cota

de Caza resized for libertarian futurist

philosophers strung out on mobilty. Powered

by economics and an insatiable primal

urge to spread

out, Dr. Green rockets by me punching

a Turbo 400 Buick Grand National into

the endgame of the Big Bang.

An

unanticipated coherent question pops

out of my mouth. "Shouldn't

we be focusing on the sustainability of

higher-density cities?" I

look behind me to see where the voice

came from.

"Most

people don't want to live in cities anymore," Green says. "Cities

create faster social disharmonies.

Riots spread faster. Pollution is in a higher concentration."

I

look out my office window. There's a gas station (CARS), a backed-up

metered freeway

onramp (MORE

CARS), an overpass

(EVEN

MORE CARS),

and beyond that tract homes in every

direction

(CARS TO THE EXTREME). I see no

human face.

"I

don't believe we're addicted to the car," he says.

Green

and I are clearly wasted.

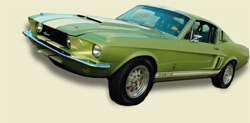

Below

me — like a three-grain shot — a

1967 Shelby Mustang GT 350 in mint condition makes a turn out

of the parking lot. On

its rear passenger-side window is a sign that reads "FOR

SALE."

As

if in the expanded seconds of a car crash, my mind races between

my loyalties to the old order, my responsibility

to

taxpayer interests

in GM’s recovery, and an addict’s rationalization

that this may be the best of all highs – snorting the

ashes of Ford — the enemy and one of the founding fathers

of the American industry. As

if in the expanded seconds of a car crash, my mind races between

my loyalties to the old order, my responsibility

to

taxpayer interests

in GM’s recovery, and an addict’s rationalization

that this may be the best of all highs – snorting the

ashes of Ford — the enemy and one of the founding fathers

of the American industry.

Inside

my head a neon sign flashes, "YOU'VE

GOT TO HAVE THAT MUSTANG."

I

drop the phone, run downstairs, and jump into my baby. With a

sharp left, I'm in pursuit,

zipping by Old Town Irvine

and

its blacksmith-shop

theme restaurant. Strip-mall history offers the locals

a romantic image at the area’s history. They eat fries

and burgers under horseshoes, next to a blacksmith's forge,

basking in suspended disbelief

about the dangers of cholesterol as well as their denial

that transportation in the days when a horse was an urban

necessity smelled like shit.

Imagine

a horse-drawn metropolis on a rainy day, the street bubbling with

the stanky gumbo of ass

goblins; on a summer

day, the unscooped,

infected fecal ooze dehydrating and crumbling into a

fine dust rising burnished into the air, coating everything.

Within that

environment,

the car became our junkie Jesus of locomotion — the

savior and tempter of our muddy urban souls.

Before

its advent, thousands of dead horses were carted from

our city streets each year — unless, as often

happened, municipal street sweepers struck, stayed

home or stayed drunk. In that case,

decomposing corpses — spinning with flies — dished

up tongue and anus feasts for ravens.

What

did the future look like in 1890? Statisticians predicted

that by 1940, people living in densely populated

cities

would be up to

their knees in horseshit.

Rolling

through the yellow light at Culver Drive, I follow a different

horse — the

Shelby Mustang. In its contoured body is the

narrative of a hot romance…a torpedo full of adventure

for a twisted new age that promised to deliver us

from air pollution, congestion and death. Yeah. Now I’m

feeling better.

The

Mustang rolls into a carwash. What the hell: There're bugs on

my windshield and parkway

sprinkler trails

on my hood. I

can get

a wash, meet the owner and score the Shelby all

at the same time. I pull up to the vacuums, leave my

key in

the car

and follow the

Mustang man to a spot under a patio where we watch

a dozen Latinos sweat and wipe the water off sparkling

hoods,

roofs, trunks,

fenders, doorjambs and windows. Thin, long-faced,

wearing

a tweed suit

and a small brimmed fedora, the mustang owner

has an unsettling resemblance

to William S. Burroughs from the dead risen.

"That's my Ford," he says before I get a chance to speak.

"How

long have you owned it?”

"It

was 1910 when the first Ford Model T came to Orange County." I

don't think

he hears my question. "All

black…squared-off…a

production line, one-size-fits-all piece

of history…the beginning

of the modern industrial age…the harbinger

of the Carnuba Sealer Wax shine," he

says "It

was 1910 when the first Ford Model T came to Orange County." I

don't think

he hears my question. "All

black…squared-off…a

production line, one-size-fits-all piece

of history…the beginning

of the modern industrial age…the harbinger

of the Carnuba Sealer Wax shine," he

says

I

flinch at the rush of precise details delivered in a measured

gravely voice. Was

this another

smug Ford

asshole

gloating

over the government-sponsored new GM’s lack of foresight?

"How

much do you want for your car?" I ask.

He

shivers.

"Henry

Ford cut the Model T's original price in two, because he wanted

everyone to own one… get them

hooked… even

farmers. Their wheelbase is exactly

as wide as a horse-drawn wagon's."

"So

what?" I say.

The

Mustang man pauses and looks me in the eye. "They

fit right into the ruts already worn into the roads. The suburb

and the car

were the perfect bump…a

synchronized transmission. During

the honeymoon,

the future looks limitless."

I

smile impatiently. "How

much do you want for your car?"

He

still doesn't answer.

"Bill?" says

someone whose shirt is embroidered with the name "Ramon."

The

man who looks like Burroughs gives Ramon his receipt with a

tip and gets into the

Mustang.

"Is your car for sale?" I ask.

"No," says

Bill, who's already beginning to drive away.

I

stare down at the ground, exasperated. Through a crack in the

pavement, glistening

with soapsuds and Armor-all, a spike

of green

stares back. It's

a sprout rooted in the best agricultural land in America — the

grade-A fields and orchards buried under the asphalt here

at the Irvine Auto Spa. This could be a remnant

of the walnuts, strawberries,

asparagus, oranges, corn, tomatoes, bell peppers, beans

and sugar beets worked by Ramon's ancestors. “Ready” he

says. I hand him seven

crumpled dollar bills and start my engine.

—

Things

aren't so limitless when I get on the

Santa Ana Freeway.

It's

jammed.

Every

new

northbound lane

all the way to the

Orange Crush — a

world-class entanglement

of freeway intersections

where the main

arteries between

San Diego

and Sacramento

wrap around one

another,

strangling the

flow of commuters

in

their quest for

a mythic ever-expanding

market — is

locked up with

heavy metal. No

matter

how much road

we have, we always

need more.

Ahead

of me, a

lifted Toyota

4Runner signaling

in a frenzy,

attempts

to change lanes.

A Lexus doesn't

want

to let

it in. Over

wild honking, the lips,

fingers and

faces of contorted

frustration

are contained behind

two windshields. Ahead

of me, a

lifted Toyota

4Runner signaling

in a frenzy,

attempts

to change lanes.

A Lexus doesn't

want

to let

it in. Over

wild honking, the lips,

fingers and

faces of contorted

frustration

are contained behind

two windshields.

I

punch the auto-scan on

my radio,

seeking traffic reports

and Sig-Alerts.

"And now the news," a voice chimes in. "It may

be easier to forgive bad drivers after you've gotten even

with them. This

may be the

case for some motorists, according to a recent survey of

traffic-school participants. The survey found that 31 percent

of the participants

have sought revenge by chasing another driver,

12 percent

threw an object at an offending car, and 5 percent rammed

the car. Three

percent had loaded guns in their cars; almost 2 percent

waved the

guns at another driver. And slightly less than 1 percent

pulled the

trigger."

Outside

my Camaro the

traffic

begins to

grow horns.

A

horde of

engines growl. I get

an

icy look

from a middle-class

teen confused

wanna-be

Scarface

with an achy-breaky

haircut — the

one in the

4Runner pickup.

Will he seek

revenge? Is

he armed?

The traffic

is at a complete

stop. He stares

at me as if

it's my fault.

He revs his

engine. I

look down,

trying to

avoid locking

eyes. Then

I see it — a

black, slick,

bubbly ooze

seeping through

the floorboards.

Before I can

react, I'm

up to my ankles

in a warm

pool of oil — crankcase

drips, tanker

spills, toxic

shit — rising

off the road.

"Get

me the fuck out of here," I yell at the dashboard as my

knees

start to simmer in the muck. "We've got 4 million miles

of highways

and streets in America. Hasn’t anyone heard of

peak oil?"

Traffic

creeps

forward.

CONSTRUCTION

AHEAD,

reads

a caution-yellow

sign.

The

oil

line in

my car

hits

my waist.

The

4Runner

teen

reaches

into

his

glove

carpartment.

I

think he's

got

a

gun.

I'm

about

to

leap out

the

door,

when

someone

toots

a

horn. It's

Bill

in

the Mustang.

I

motion

frantically

for

help

as

the oil

hits

my

chest.

Bill

just

points

to

the

yellow

signs

as

the oil

bubbles

up

my nose.

"Exterminate

all rational thought," he yells out of his window

as he inches by.

It

appears we

have.

The

next few

moments are

a stretch

of lost

highway that's

been blanked

out of

my memory.

—

When

I snap

to in

a Harbor

Boulevard gas

station minimart's

secured-for-my-safety restroom,

I'm

splashing water

on my

face and

rubbing my

clothes with

a cardboard

pine tree

shaped auto

air-freshener to

chase the

smell of

40-weight oil

from my

cognitive memory.

Outside, in

the afternoon

sun on

the street

corner, a

small crowd

gathers at

a bus

stop.

There

was a

time in

this country

when most

people got

to work

by foot

or by

public transportation.

In the

1930s, seven

billion commuter

trips each

year were

taken on

electric systems

like Southern

California's Red

Car line.

Where

did all

our streetcars

go?

Some

say that

the oil,

steel and

rubber industries — trying

to heighten our addiction to the automobile — bought

the lines and plowed them under (see Who Killed

Roger Rabbit?).

Others

say those

same industries

invested in

electric-powered

mass

transit only

to discover

the systems

were falling

short of

our transportation

needs (see Alice in

Wonderland).

For

whatever reasons,

General Motors,

Firestone Tires,

Standard Oil

and Mac

Machinery bought

out more

than 100

electric rail

lines in

45 American

cities over

13 years.

By 1950,

90 percent

of those

were destroyed,

including the

Pacific Electric

from Los

Angeles to

Santa Ana.

Now, in

its place,

we have

GM’s legacy — miles

of congested roads.

I

return the

restroom key

with its

miniature tire

fob to

the clerk

at the

counter and

browse the

magazine rack. Car and

Driver, AutoWeek,

Motor Trend,

Hot Rod,

Car Collector,

Car Craft. Next to Muscle Car

Review, I

spot a

pamphlet titled "Solutions

for an Auto-addicted Orange County."

"You can have a wonderful life without a car," it reads. "Get

in shape. Lose weight and increase cardiovascular fitness.

Save money. The average price of a car in Orange

County

is $21,544, and

it begins to depreciate in one day. Breathe easier. Cars

are the major source of air pollution."

There's

a phone

number included:

(949) 452-1393.

Is this

a message

from the

god of

public transportation?

Have I

found my

cure for

pain? There's

a phone

number included:

(949) 452-1393.

Is this

a message

from the

god of

public transportation?

Have I

found my

cure for

pain?

I

rush outside

and fumble

for change

at the

pay phone

as the

bus-stop crowd

watches me

miss-dial, dial

again, miss-dial,

dial again.

A drunk

had plowed

down the

cellphone tower

on the

corner earlier

in the

day. The

signal-less Bluetooth

in my

left ear

clacks annoyingly

against the

heavy plastic

receiver cradled

between my

head and

shoulder. I

worry about

the ergonomics

of the

situation.

At

last, Jay

Laessi of Auto-Free Orange

County answers.

"I'm addicted to cars. What can I do?" I say.

"Try walking…first try walking," says Laessi

as if he handles 100 calls like mine every

day.

"Where?" I say. "I'm surrounded by cars."

"Orange County is one of the worst areas in the country

for that," he

says. "But if you can’t

walk, try taking a cab. They're $1.90 a mile.

If you can share one, it's even better. Or get

on

a bus."

Maybe

I should,

but I'm

apprehensive. How

will this

help taxpayers

get a

respectable return

on

our

government-mandated

investment

in

the American

auto industry?

"No,

thanks. No bus. Mass transit can't work in the suburbs," I

say, avoiding the real issue. "Southern

California is too much

of a sprawl for public transportation to work.

There's no central point of departure."

Laessi

disagrees.

“Smart people ride mass transit,” he says. “You

can get your work done, read a book or meet

someone. The first step is to

call 1 (800) 636-RIDE.

Can

you hold for a second?"

Before

I can

answer, I

hear another

number being

tone-dialed.

"Thanks for calling the Orange County Transportation Authority," a

new voice says. "Can I help you?" Laessi

has forwarded me through to bus-route information.

I freeze and babble something

into the phone. A minute later, the sweet voice

at the other end

of the line has informed me that OCTA can get me

home in 30 minutes.

30

minutes. Am

I kidding

myself? I’ll miss my drive-time junk:

my daily two-hour taillight tripsomania. I’m

in hurry. Let the man go through. The

smell of

fresh asphalt

wafting across

the street

from the

new right-turn-lane

replacing the

sidewalk

grips

me like

the dry-heaves.

“30 minutes,” the transit authority operator’s

kindness calms me. I can do this. I join the crowd at the

bus stop. They

eye me suspiciously at first and move imperceptibly away.

I know we’ll

grow to be friends eventually. If you're going to break

a habit, you have to get hooked on something

else.

—

Waiting,

watching cars,

a chill

hits my

body. I

do a

wet-dog shake

as an

engine hums

in my

ear.

It's

Bill. This

time he's

driving a

1959 seagull-wing

Chevrolet

convertible – a

throwback

to GM’s

golden days.

"'Give to every people of every land better roads and more automobiles,

and we shall do away with most of the ill will that exists between human beings,'" he

says mockingly. "Some

jackass named Irwin Cobb wrote that in 1923. He

believed that World War I wouldn't

have happened if the

world had more cars." "'Give to every people of every land better roads and more automobiles,

and we shall do away with most of the ill will that exists between human beings,'" he

says mockingly. "Some

jackass named Irwin Cobb wrote that in 1923. He

believed that World War I wouldn't

have happened if the

world had more cars."

"Really?" I say. Silently I wonder. Was Cobb alive

to see WWII? What would he have thought of

this new millennium, where American

need for petroleum-based mobility secured an involvement

in seemingly endless foreign conflicts? Would

he have thought

the American auto

industry deserving of redemption in the form of a bailout?

Bill

looks me

up and

down. "You

need a lift somewhere?"

I

hesitate.

Shouldn't

I get

on the

bus? Don't

I want

to

kick

the habit?

"Are

you going to pass up a ride in Mr. Fin's first Chevrolet?" Bill

asks.

I

have no

idea what

that means,

but before

I know

it, I'm

heading south,

lost in

the huge

expanse of

the Chevy's

red-and-white interior.

"What happened to the Mustang?" I ask.

"Who

needs that shit?" Bill says. “I’m a Chevy man.

With fins like these, I can peel the skin off a bag lady. You

can thank Harley Earle for that. General Motors hired him in the

1930s

after seeing the custom cars he designed in Hollywood. At GM,

Earle reached down into the cars' guts and pulled out a personality.

They

called Earle "Mr. Chrome." One of his protégés — Bill

Mitchell — became

'Mr. Fin.' He cooked up this Chevy.

"GM had Earle making major design changes every year. Without this

year's model, you were yesterday's news. He called it 'dynamic obsolescence.'

General Motors called it huge profits."

We

wait at

the onramp

of the

5 Freeway

to cheers

of pedestrians.

The gull

wing generates

its own

audience. It's

Pop sculpture

on wheels.

"Earle's beautiful machines crept through traffic nightmares

in the 1930s," Bill says, sliding into the free-flowing

eastbound traffic. "Southern

California had streetcar-scale downtowns packed with

GM cruisemobiles. It was a mess."

Bill

reaches into

the glove

compartment

and

pulls out

a copy

of Los Angeles

Times dated

1938.

"Where the hell did you get that?" I say.

"Shut up and listen. The automobile, which was 'designed to be the

emancipator of man,' was 'defeating its own purpose,'" he reads

to me, slapping the paper for emphasis. "'Man

is being enslaved again by the servant he created.'

"So what did L.A. do? Lloyd Aldrich, a city engineer, pushed through

a plan for 600 miles of multilanes penetrating downtown. Right then and there,

the fast-lane lifestyle was born.

"When

the car and the city merged, urban energy was sucked away.

Cities became diluted…borderless.

A crisscross concrete grillwork defined Southern

California, scattering businesses and homes to

places ruled by the car.

Dynamic obsolescence described our way

of life.

Southern

California became

a microcosm

of suspended

disbelief, an

object lesson

in pushing

a flawed

plan forward

on the

specter of

aggressive market

expansion — manifest

destiny without

regard for

the

realities of resources.

Through

the Chevy's

huge windshield,

tract homes

and strip

malls float

by. We're

above the

flatland

of

Orange County

on the

elevated, quater-mile

long carpool

lane linking

the Interstate

5 to

State Route

55

southbound.

Bill continues.

"Cramped non-ethnic Californians were enchanted by the spectacle

of Motorama during the '50s and into the early '60s; it was GM's car-show vision

of tomorrow. At the Pan Pacific Auditorium in L.A.,

a scale-model of a future metropolis paraded cars through pollution-free air-tight

Corbussier vistas.

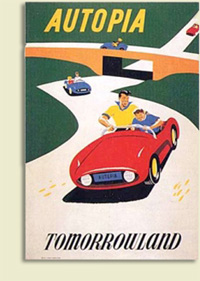

"That was the blueprint," he says like Rick Warren

in a self-possessed rant. "In

1955, the blueprint was made real with the opening

of Disneyland and the

Santa Ana Freeway. Some people thought Disneyland

would be a permanent

world's fair. I say Orange County is Motorama." "That was the blueprint," he says like Rick Warren

in a self-possessed rant. "In

1955, the blueprint was made real with the opening

of Disneyland and the

Santa Ana Freeway. Some people thought Disneyland

would be a permanent

world's fair. I say Orange County is Motorama."

We

cross five

lanes of

traffic in

less than

a half

mile to

glide onto

Interstate

405

south,

flashing

by the

blocks of

steel, glass

and concrete

that

is

South Coast Plaza. The

1959 Chevrolet

feels like

an E-ticket

ride.

"Even our goddam president started pushing the car," Bill says,

attempting an impression of Dwight David Eisenhower: "'Automobiles

mean progress for our

country, greater happiness and greater standards

of living.' That's what Ike said.

"Congress agreed and laid down the cash for the construction of a

system of interstate highways. It was a public-works scam as big as anything

FDR finagled, but with a 1950s propaganda spin.

"With the Soviet Union supposedly ready to drop the Big One on us,

the Feds said new freeways could be used to transport troops and evacuate the

population. I guess we were supposed to believe that

when the commies launched the H-bomb, we could jump on the 99 and be in Barstow

in time to watch the fireworks."

This

isn’t the version I remember hearing in the chrome and

formica booths at Cantor’s Deli in my youth, but Bill

was

on a roll: Interstates created a colossal, taxpayer-funded sprawl.

Automobiles powered our move to the suburbs — the largest

migration in U.S. history. I was part of that move when

Orange

County became my home. On my last day of citizenship in Los

Angeles — my

last hour — I

sat in the parking lot of the Chevrolet Plant

in Van Nuys where I worked.

My eyes stung. The air was green with smog and

tasted like dirt. I left and

took

it with me. As I headed out of LA, a 40-foot tall

cat with glowing green eyes maintained his vigil

over Felix Chevrolet, smirking down

at me as though I

missed the joke.

“People didn't want to live in cities anymore."

"Bullshit," Bill says. "The planners of this sprawl

could have been visionaries instead of pimps.

They could have been leaders

and shown some courage. Instead, those assholes developed

land faster than a $2 blowjob."

Today

you have

to spend

$30 in

gas to

drive into

LA for

a decent

$40 hand

job. Just

ask Charlie

Sheen.

As

Bill brings

the Chevy

to a

stop in

front of

my car,

I realize

we've been

traveling in

a circle. "Hasta la vista," Bill

says.

"I don't want to drive anymore," I say in a panic.

Bill

laughs. “Get out and face your fears," he

says.

I'm

only half-way out the door when Bill jerks the car

away, spinning me stumbling through the mini-mart

lot. Hissing rubber

on

pavement, the Chevy's

low rumble fills the

night air — it's

gull wing disappearing

into Harbor Boulevard traffic. I find my Camaro,

slip

inside, breathe deeply, and drive.

—

On

the ride

home, Bill,

Dr. Green

and Laessi

do battle

in my

head. I

don't care

if the

car is

a primal

instinct or

the end of a

hypodermic. I

have a

duty to

break the

chain — clear

up my country, the economy,

my lifestyle.

Up

the driveway,

in my

suburban

garage,

my Camaro

is

secure and

serene — but

I'm

jacked.

I flip

on

the

TV

and

channel-surf

the

news.

There's

a gang

shooting

on

Olympic

Boulevard

and

a

follow-up

report

from

a previous

drive-by

in Compton.

The

local

news

codifies

a message:

high-density

cities

are

dangerous,

while

the

crabgrass

frontier

is

safe.

It's

easy

to

watch, closing

your

eyes

to

the

peril:

Underestimating

the

risks

of driving

and

overestimating

the

risks

of

crime.

The

auto-dependent

family

nestled in the

hills of Rancho Santa

Margarita will never

admit that BMW is

more

of a menace to

society than N.W.A

ever was. Yet, automobiles

and auto accidents

lead

to more deaths and

injuries in suburbs

than guns

and

drugs

do in cities.

On

the 11

o'clock news,

the video-clip

pool of

blood spreads

from a

chalk-body silhouette

in

South-Central,

not a

crash on

El Toro

Road. Between

each news

segment, a

different car,

a different

make, a

different

model

advertises an

endless expanse of rural

roadway, signifying

the only

way

out

of the

theoretical urban

hell.

I

aim and

shoot. The

TV's off.

—

A

week passes.

No cars.

I think

I’m

clean. But I need to test myself.

This

morning,

I

walk on

carpeting

milled to

resemble

roadways

and

intersections — a

black

low-pile

with

lane

stripes.

Automobile

logos

hang

from

above.

On either

side

of me,

beyond

the

Scotch-Guard

road,

are

cars.

Here,

at

the

California

International

Auto

Show

at the

Anaheim

Convention Center,

is a

Motorama

for

the

new

millennium.

"There's so much to see," I hear an overjoyed woman

in a Dodge Hemi T-shirt and fanny pack exclaim.

In

the air-conditioned

auditorium, surrounded

by these

quiet and

motionless exhibits

of contemporary

auto culture,

I feel

like an

academic, successful

in isolating

my subject

from its

environment. Here,

it's easy

to believe

that Dr.

Green is

right. Like

a transportation

diorama at

the Museum

of Science

and Industry,

the automotive

display is

located right

next to

the Conestoga

wagons. Engraved

plaques inform

us that

the unquenchable

appetite for mobility is

spun from

our brain's

core.

Nevertheless,

everyone at

the exhibit

looks as

if they

sense our

subjugation. The

car has

put too

many miles

between us.

It dominates.

No one

talks about

standing in

the place

where they

live and

making it

better.

"It’s

harmony between man, nature and machine," announces

a woman in a black business suit to no one in particular. "It" is

the Third Generation

Prius.

Utilitarian,

unpretentious,

easier

on the

gas and

chuck full

of “green

technology” the Prius is heroin lite – our mobility

methadone. It doesn’t cure us of our addiction, it

just makes

the dope easier to stomach. The Prius’ is user friendly and

green as a hemp shower curtain, but no one from Toyota talks about

consuming

less. It’s all about going where you aren’t,

not growing where you

are.

We

mill by

the car

that creates “harmony between man, nature

and machine" only mildly amused. But across the hall,

a crowd

pushes toward a stage. Cameras flash. Grown men and women gape.

Children squeal ecstatically. Before them is the Corvette

ZR1.

It’s

the old side of the new

GM.

I've

never wanted to drive a car so much in my life," I

hear someone say.

It's

Bill in

the crowd,

staring desperately

at the

ZR1’s

air scoop streamlined snout. A taste

of GM

metal in my mouth wakes me.

Weak with craving, I

manage to spit it out.

What

I

need

isn't

on

display

here

or

at

Motorama

or

any

Car

Dealer's

Association exhibition

anywhere.

What I

need vanished

when

America

stopped

walking, slouched

in

their

cars

and drove

away — when

we hooked

our Kerouacian

mobility

solely

to the

road and

lost sight

of everything

else.

I

stare

into

the

ZR1’s

headlights,

but it

looks past

me down

some undetermined

dark highway. “Get

in,” it

seems

to say.

I hop over

the driver's-side

door and

turn the

ignition

key.

The roar

of the

engine

silences

the hall.

"It's

time to meet the future!" I yell.

The

crowd is startled. Bill hops the barrier and jumps

in with me.

"To

the cities!" he shouts.

I’m staring into the eyes of

a dead junkie. Distorted and distant, the voice of the transit

authority operator

floats through

my frontal lobe.

“I know why you’re dead,” I say killing the

engine. Bill grins and

searches his pockets for exact change. I pull a mangled

bus schedule from my pocket.

"Blasphemers," the

crowd hisses as we abandon the display, asking directions to

the exit and nearest public transport. But they part

as if we hold stone tablets, a new set of commandments,

keys to a different

gospel.

There's

the road,

the car

and the

dynamic of

speed and

space pinning

us against

a dichotomy

of resources

and horizons.

But there’s

a life beyond this

subjugation. There’s

our hometowns,

with

neighbors and friends.

Places where

we can live free

of bankrupt

greenwashed showroom

floors.

Listen.

I

know

you’re as

strung out as

I am. Let’s

make this a

mutual intervention.

Take a cleansing

break. Push

your

hands

into the asphalt

and bring up

some

dirt. There.

It’s

good. Relax.

Take a staycation.

Visit your local

library or park

while

you still have

them. Open yourself

to the adventure

of the world

that’s

right around

you.

Think

about

the

place

where

you

live.

Wonder

why

you

haven't.

As

for

mobility,

economics,

and

ecological

sustainability,

opening

your

imagination

to

the possibilities

of

where

you stand is the

best defense

again

dynamic

obsolescence.

Your

feet

are

going

to

be on

the

ground.

Your

head

is

there

to

move you

around.

Let's

make

this thing

work.

— Nathan

Callahan, July 17, 2009

A

Clinton-era version of Hallucination

Engine appeared in The OC Weekly, March 14, 1997.

— Nathan

Callahan

|