Tobacco Road: Tom Rogers and the Phillip Morris Tollway

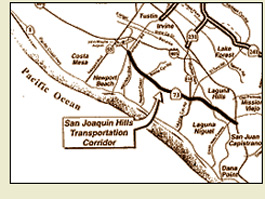

November 21, 2011 marks the 15th anniversary of the opening of Orange County’s controversial San Joaquin Hills Transportation Corridor, otherwise known as Southern California’s first tollroad. Carved through the region's pristine coastal foothills, the tollroad is a asphalt shrine to a tobacco giant's greed and suburban planning gone awry. Today, traffic and revenue on the 16-mile San Joaquin Hills toll road is lagging so badly behind projections that the managing organization for the road, the Transportation Corridor Agencies, may soon default on $1 billion in bonds. First published in the OC Weekly in 1996, Tobacco Road focuses on the tollroad's principal opponent, the late Tom Rogers.

___

I’ve been an abject failure,” Tom Rogers said as he drew an imaginary bead on the new connector bridge to the San Joaquin Hills Toll Road.

“No you haven’t. . . .” I replied, but his laughter cut me short before I could dig his ego out of abjection.

“Shit, just look,” he said. “Shit, just look,” he said.

Under construction at the intersection of the San Diego Freeway near San Juan Capistrano, the bridge angled north through carved-up terrain. Fresh asphalt painted a line of black into the distance through the countryside. Running 15.5 miles and $800 million from where we stood north to the city of Irvine, the toll road’s construction is the prize of a decades-long war. The victors? Corporate superpowers, chief among them the Philip Morris companies.

“What they learned in the cigarette business,” Rogers said, “they brought to real estate.”

Yes, the purveyor of Marlboro, Benson & Hedges and Parliament cigarettes; buyout owner of Miller brewing and General Foods (famous for such delectables as Kool-Aid, Jell-O, Maxwell House Coffee and Bird’s Eye frozen foods) is also the proprietor of the Mission Viejo Company.

The once unpopulated area, now transversed by the road, demonstrates how our county government serves corporate progress and land development — not voters. Crosscutting Laguna Canyon, the Louvre of Southern California coastal flora and fauna, the toll road is a testament to the insolence of the few, the shortsighted, the powerful.

“It only hurts when you laugh,” Rogers said, laughing some more.

In the battle over if, how, and where the road would go, Rogers has been defeated more times than he cares to think about. But he’s not the only loser. To date there are 2,602,543 others — every Orange County taxpayer.

___

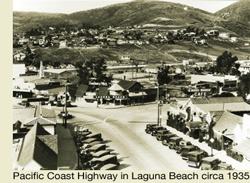

The origins of this battle appear innocent. In the early 1960s, the state of California proposed widening Pacific Coast Highway through Newport Beach south to Dana Point. Residents along Orange County’s coastal communities rallied against the plan with fierce, provincial loyalty. Mounting a grassroots campaign, they perceived the widened highway and the traffic it would shuttle through their towns as rural desecration.

Like Rogers, these were conservative folk — the Junior Women’s Club of Laguna (mostly Republican, prim and proper), the Laguna Chamber of Commerce (a mainstay of local commercial interests) and city officials from Newport Beach. Together they staged a public demonstration against the state’s roadway plan. Like Rogers, these were conservative folk — the Junior Women’s Club of Laguna (mostly Republican, prim and proper), the Laguna Chamber of Commerce (a mainstay of local commercial interests) and city officials from Newport Beach. Together they staged a public demonstration against the state’s roadway plan.

Establishing a spirit of eccentric contrariety years before longhaired Laguna Beach hipsters raised their leftist fists and fingers against the conservative established order, Orange County’s upstanding citizens lined up across PCH, singing and blocking traffic. The new roadway was defeated, but the fight had just begun.

To the north a potpourri of riots, poverty and urban decay intensified the anxieties of middle-class families. It was the 1960s and the market for safe havens was growing faster than real-estate developers could find virgin soil. The earliest developments, cobbled together from asphalt grid and wood frame in southern and northern Los Angeles County, were being swallowed up by LA’s material and metaphysical borders.

Across the county line the story was different. With a Father Knows Best appeal, Orange County beckoned to the urban-weary. A 786-square-mile wonderland — complete with small towns and Disney’s dazzling theme park — it was predominantly safe and not too far off-white. The air was clean, the beaches pure, and poverty hidden or scarce. Orange blossoms scented the air. No inner-city minorities plotted uprisings, no high-rises blocked out the sun, no traffic or congestion muddled the roads. Life was uncluttered, conventional and small-town conservative. While Los Angeles’ suburban sister, the San Fernando Valley, was a boiling, carbon-monoxide-filled pothole, Orange County was a glimpse into the great wide open . . . Marlboro Country Lite . . . the promised land. Across the county line the story was different. With a Father Knows Best appeal, Orange County beckoned to the urban-weary. A 786-square-mile wonderland — complete with small towns and Disney’s dazzling theme park — it was predominantly safe and not too far off-white. The air was clean, the beaches pure, and poverty hidden or scarce. Orange blossoms scented the air. No inner-city minorities plotted uprisings, no high-rises blocked out the sun, no traffic or congestion muddled the roads. Life was uncluttered, conventional and small-town conservative. While Los Angeles’ suburban sister, the San Fernando Valley, was a boiling, carbon-monoxide-filled pothole, Orange County was a glimpse into the great wide open . . . Marlboro Country Lite . . . the promised land.

Irvine was the first of the new Elysiums. Recognized in the late 1970s by Business Week as “America’s biggest real-estate project,” development began ambitiously in 1960, when eccentric Joan Irvine Smith, a descendant of the august Irvine ranching family, hired architect William Pereira to draw up a master plan. To execute Pereira’s concept — a structured monochromatic 1960s ideal of family living — she called on friend and former Navy Secretary Charles Thomas.

Farther south, another empire was in utero as future Irvine Company Chairman Donald Bren mated with Dick O’Neill of Democratic Party fame. In 1963, they snipped off a bit of O’Neill’s ranch and the Mission Viejo Company was born. Farther south, another empire was in utero as future Irvine Company Chairman Donald Bren mated with Dick O’Neill of Democratic Party fame. In 1963, they snipped off a bit of O’Neill’s ranch and the Mission Viejo Company was born.

Bren had spent his boyhood summers bathed in the light of wealth, frolicking along the Irvine coast. He was a fortunate well-connected son. Milton, his father, was a Hollywood producer (the Topper films and other lightweight fare). Actress Claire Trevor was his stepmother; his stepfather, industrialist Earle Jorgensen, was chummy with Ronald Reagan.

On his path to building a fortune, Bren saw Mission Viejo as a mere stepping-stone. Four years and millions of development dollars later, the 11,000-acre planned community was up for sale, and Philip Morris — a faceless multinational seeking to diversify — bought it. The South County real-estate boom was on.

There was, however, a problem. It would be child’s play attracting customers to the product — fresh real estate in a relatively controlled and sheltered setting, but how would the clientele get to and from the purchase point as development moved south? What about roads, which were already lagging behind the County’s steady growth?

Pavement was needed. Miles and miles and miles of it.

___

While the bulldozers of Mission Viejo and Irvine rumbled in the north, Rogers saddled up his horse Duke (“named after no one in particular”) and set out across the rolling hills and valleys of what is now Laguna Niguel and Aliso Viejo — land he leased for his cattle.

Born in San Francisco on December 26, 1924, Thomas C. Rogers has no use for pomp, arrogance, dishonesty or snakes. A straight-talking conservative, the quintessential California rancher, he is to John Wayne what Jim Lovell is to Tom Hanks — the genuine article. Ranching was his lifelong ambition.

On Rogers’ spread, just west of Mission Viejo, water was a precious commodity. In the summer, he would drive his herd a few miles inland to a spring at the head of Salt Creek, which meandered a few miles and emptied into the Pacific Ocean near Monarch Bay. “It was a nice little draw there, a gorgeous slice of nature,” Rogers told me. “In the evening all the animals would come down — deer, Canadian honkers, sandhill cranes. It was the only sure source of water year-round.”

On one such visit to the spot, Rogers noticed developers grading for homes nearby. He rode over to see what was up and befriended the bulldozer operator. The two of them — Rogers on his horse, his friend on his yellow machine — spent many afternoons killing time in conversation as the cows maneuvered for drinks.

Weeks passed, and the hillsides metamorphosed into Mayan-like pyramids of vacant lots. As the work gradually neared his cattle’s grassland, Rogers suggested to his bulldozer friend that the spring could be valuable to developers. “They could probably make a hell of a lot more money selling homes with a view of the springs,” he said.

A few days later he rode back to his favorite watering hole and was stunned. “They had gone in and wiped that sucker out,” he said. “I mean they took all the trees out, leveled it, filled it in and tamped it down. In my own country-boy way of thinking, I couldn’t understand why they’d do that. They could have made more money and saved a precious resource. But all they wanted was density. A few days later he rode back to his favorite watering hole and was stunned. “They had gone in and wiped that sucker out,” he said. “I mean they took all the trees out, leveled it, filled it in and tamped it down. In my own country-boy way of thinking, I couldn’t understand why they’d do that. They could have made more money and saved a precious resource. But all they wanted was density.

“We lost a tremendous asset. Nowadays, they make concrete lakes with chlorine in the water and put in a cement bird.”

The destruction of the Salt Creek spring changed Rogers. “Every rancher is at least a passive environmentalist,” he said. “You have to be to stay in business. But that day marked a turning point in my approach to the environment. I turned from being passive to active.”

That personal transformation marked a turning point for Orange County as well. Rogers was a political insider. He knew more than one kind of turf. In the mid-1960s, he was the finance director of the Orange County Republican Party. From 1969 to 1972, he was its chairman.

According to Larry Agran, former Democratic mayor of Irvine, Rogers “is a figure of historic proportions . . . an astute observer and a key participant in Orange County politics for an entire generation.” But in Rogers’ own stories about his role in the County’s GOP, he emerges as a relatively minor personality.

These stories are peopled by characters out of Floyd’s Barbershop in Mayberry, mostly close-knit townsfolk. The anecdotes explain something of Rogers’ politics, too. Take, for example, his memory of Walter Knott, the paterfamilias of Knott’s Berry Farm and an archetype of conservatism. Knott was, according to Rogers, a man with a mission, but a man who would never try to pull the levers of government for his own business ends. In those days, Orange County’s model citizens gave back to the community with no expectation of a return on their kindness.

Like Knott, Rogers explains, they would have equated a personal favor from a government official with “welfare for the .”

But welfare for the wealthy was exactly what lay ahead for Orange County. Inextricably connected to the type of development that buried the Salt Creek spring was a plan for a road that would run north and south, joining the San Diego Freeway at points 15.5 miles apart. It was the latest rendering of the thoroughfare that Laguna’s blue bloods had defeated a decade before. Now county mapmakers had moved it inland from Pacific Coast Highway, across the first ridge and into the pristine San Joaquins — some of the last coastal foothills in Southern California.

The location of the road was proof that it was not there to alleviate traffic; it didn’t go where people needed to go. It would run from one sparsely populated community to another, through land dominated by coyotes, deer, rabbits and cattle. Rogers’ conclusion? The road was a kind of mainline for high-density development — the sort that had obliterated his “slice of nature.”

That made it a government gift to private enterprise — a handout, something Tom Rogers abhorred. Animated by the destruction of the Salt Creek spring, Rogers decided to fight the San Joaquin Hills Road.

On his first visit to an early public planning meeting conducted by the County, he noticed something curious . . . even ominous.

“First thing they did was show us Choice A. It was a grapevine road from Irvine to San Juan Capistrano that violated some construction guidelines. Then they showed us Choice B. It was straighter and didn’t violate the codes. Then they said, ‘Which one do you want?’ Well, one smart guy in the back got up and said, ‘We want the third option — not to have the road.’” Rogers joined the others shouting their approval of the third option. “But the county guy just said, ‘I don’t know anything about that.’” “First thing they did was show us Choice A. It was a grapevine road from Irvine to San Juan Capistrano that violated some construction guidelines. Then they showed us Choice B. It was straighter and didn’t violate the codes. Then they said, ‘Which one do you want?’ Well, one smart guy in the back got up and said, ‘We want the third option — not to have the road.’” Rogers joined the others shouting their approval of the third option. “But the county guy just said, ‘I don’t know anything about that.’”

“Right from the beginning, it was a done deal,” Rogers concluded. Despite what the people wanted, there would be a road.

___

The Shooting Star set sail from Cabo San Lucas in Baja California on Sunday, June 10, 1974, on a leisurely trip up the coast to its home port in Orange County. Among those onboard were Fred Harbor, a county campaign manager; Tom Klein, executive assistant to the Board of Supervisors; Leonard Basher, an Anaheim contractor; and Ron Caspers. Caspers had just been re-elected to the Orange County Board of Supervisors, and this celebratory fishing cruise offered cool-down time after a long campaign. But four days after the boat set sail, it encountered rough seas near San Benito Island. Hours later, the U.S. Coast Guard monitored this message:

“Shooting Star. Mayday. Mayday. Request all vessels in the vicinity attempt to assist.”

The passengers and crew were never heard from again.

Caspers’ death presented then-Governor Ronald Reagan with an important decision. Who would he appoint to the vacant seat on the Orange County Board of Supervisors? After all, the County had provided the governor with boundless political support. And (say no more) he had important friends in the development community. For a county beginning to exert influence on state and even national affairs, the appointment would carry prestige, clout and career potential. Caspers’ death presented then-Governor Ronald Reagan with an important decision. Who would he appoint to the vacant seat on the Orange County Board of Supervisors? After all, the County had provided the governor with boundless political support. And (say no more) he had important friends in the development community. For a county beginning to exert influence on state and even national affairs, the appointment would carry prestige, clout and career potential.

There was a trumpeting herd of Republicans awaiting Reagan’s phone call. Few of those appeared less likely for the job than Tom Riley — which made him the perfect choice.

Riley was a man who seemed to stumble into success. He had little experience in government or politics. Early in life at Virginia Military Institute, a miraculous lurching touchdown run and the resulting loss of a front tooth earned him hero status — and the nickname “Mugs.” He entered the Marine Corps in 1935, rising through the ranks to become a brigadier general. Retiring 29 years later, he and his wife settled into a Back Bay, Newport Beach home. By 1974, Riley was working for a military contractor and — according to the official story — was slowly withdrawing from public life. It was reported that when he received his call from Reagan on a Sunday afternoon in late August 1974, Riley was lounging on his back porch.

“I was shocked,” Riley told Los Angeles Times. “I didn’t have any idea why the governor would be calling me.”

Would he want the job on the Board of Supervisors?

“Yes.”

How much time would he need before the announcement was made?

“Seventy-two hours.”

“Make that 24,” said Reagan, and Riley was on the job. The next day Riley made three calls. One to a retired Los Angeles congressman. One to the mayor of Newport Beach. And one to Charles Thomas — president of The Irvine Company.

That last call is curious, don’t you think? Riley has never said publicly what the conversation was about. The two may have talked about their days together in Washington, D.C. They may have reminisced about Cosmo Topper. My guess is they discussed the future of South County development and roadways — and what that meant to the Board of Supervisors.

Whatever he and Charles Thomas talked about, Riley turned out to be a real-estate developer’s dream and an apostle of the gods of growth and development. For the next 20 years, he remained on the Board, working out what he thought was the divine providence of rapid growth. And he did it with the zeal of a military man. Whatever he and Charles Thomas talked about, Riley turned out to be a real-estate developer’s dream and an apostle of the gods of growth and development. For the next 20 years, he remained on the Board, working out what he thought was the divine providence of rapid growth. And he did it with the zeal of a military man.

“Until I became a county supervisor,” he told the Times, “I thought everybody loved me. In the Corps, I’d say something, and they’d say, ‘Aye, aye, sir.’ Nobody argued.”

Aye, aye, sir. Full speed ahead with development. Orange County was in for a tempest.

North of San Juan Capistrano, the hillsides must have looked like realty heaven to development tycoons — especially with the promise of a road and the presence of Riley and his like-minded colleagues on the Board of Supervisors. With the Mission Viejo and Irvine companies showing big profits, other Orange County land barons considered conversion from cattle operations to planned communities. The Moulton family was one of them. What the longtime Orange County clan had in mind for their ranch west of Mission Viejo and east of Laguna Beach was low-density pocket developments totaling around 10,000 homes. With the right zoning, the land would be worth close to $55 million. Money and housing units were beginning to sound much better than vacant land and cattle scat.

The Moultons took their plans to the County. Soon, government wheels began to grind. Inspectors and planning officers scheduled a sound study to determine if the ranch was suitable for residential zoning. Out came the omnidirectional mikes. The decibel readings were set. The VU meters were flat. And the Moultons waited.

But, lo, out of the still came a roar. Jets en route to nearby El Toro Marine Corps Air Station had pegged the pin. The VUs peaked. The experts concluded that El Toro jet noise over part of the hoped-for planned community exceeded the sound limit. Translation: no deal, no homes, no $55 million. The County’s finding rendered the land nearly worthless to developers.

Until that time, Philip Morris had confined its real-estate ambitions to the east side of the 405 Freeway, where it was building out Mission Viejo. But the Moultons’ disappointment provided the tobacco giant with an opportunity to move farther west. In 1976 it did, snaking across the 405 and snapping up the land for $5 million. Soon after, Philip Morris appealed to county officials regarding the sound-level findings on the land it had renamed Aliso Viejo.

“That property was only worthless to somebody who didn’t know county government,” Rogers said. “That property was only worthless to somebody who didn’t know county government,” Rogers said.

Philip Morris knew county government. The company “ordered another set of sound studies and guess what?” Rogers asked. “Why, it wasn’t noisy at all. That’s how they got over on this side of the freeway and involved in the road.”

___

This, then, is the beginning of Tobacco Road, and Rogers tells it with a sense of burlesque. He laughs often — at himself, at the audacity of Philip Morris, at county officials who looked dumb and played dirty politics. With Philip Morris as landowner, development plans for Aliso Viejo doubled from 10,000 to 20,000 homes. The dun-colored hillsides were approved for dun-colored homes. Profits would be huge. There was only one problem. Aliso Viejo was landlocked — surrounded by other cities and serviced by few roads. In order to extract the full value of their investment, a mega-road had to be built. And Philip Morris, as the Moultons had sadly discovered, knew how to get a great deal.

The Irvine Company and its owner, Donald Bren, are traditionally the primary target of anti-growth wrath in association with Tobacco Road. But Bren’s planned communities were adequately serviced by the 405 and 5 freeways, and east-west arteries to the Irvine coast were in the works. This didn’t mean that Bren would oppose a major thoroughfare across his property. He’d love it. Development begets development, and nothing jump-starts the begetting cycle like a road. So, The Irvine Company promptly let it be known that they would do nothing to stand in Tobacco Road’s way.

The pieces were in place for the next big purchase. Philip Morris had Aliso Viejo: the motive. It had Don Bren’s approval on the right of way through Irvine Company property: the opportunity. Now, it needed the means to build the road: the Orange County Board of Supervisors.

___

“You could spend the rest of your life writing this story,” Rogers said as we approached his home, back from our walk to the toll road viewpoint. “There were so many complications. Back in 1977, it was a foregone conclusion: The road would be built. The skids were greased.”

Since 1977, the development community contributed a staggering total of $3.7 million to supervisorial candidates who “shared their philosophy”: The doctrine that building out Orange County as quickly as possible, and getting taxpayers to pay for incidentals like Tobacco Road, was more important than the inconvenience of democracy. This lopsided contribution sum accounted for 42 percent of the Board’s campaign bucks, more than the finance industry, the legal community, the tourist trade, the manufacturing industry and organized labor combined. Since 1977, the development community contributed a staggering total of $3.7 million to supervisorial candidates who “shared their philosophy”: The doctrine that building out Orange County as quickly as possible, and getting taxpayers to pay for incidentals like Tobacco Road, was more important than the inconvenience of democracy. This lopsided contribution sum accounted for 42 percent of the Board’s campaign bucks, more than the finance industry, the legal community, the tourist trade, the manufacturing industry and organized labor combined.

With this much money targeted to developer-friendly politicians, Rogers saw Orange County’s future, and he didn’t like it. “This wasn’t a partisan issue and never was. There are corporate rights, and there are personal rights. The individual citizen has rights, just as the developer has rights. One shouldn’t overwhelm the other.”

Rogers’ brand of conservatism favors a balance between individual rights and property rights. As he saw it, the danger to the County was clear: The power of granting development rights — and ultimately the toll road’s construction — was in the hands of the supervisors whose campaigns were being financed by private-property zealots champing at the bit to build out the County as quickly as the market could bear. Never mind the County’s rich agrarian past, its rural charm, its sense of community, its conservative demeanor. The question now was not how best to grow, but rather how fast and how profitably.

___

It’s now fairly commonplace to find similarities between the New Left radicals who rose up in places like Berkeley, Columbia and Michigan in the 1960s and conservatives like Tom Rogers. Both have a mistrust of big institutions — corporate or governmental. Both have a faith in the power of the individual to change history.

Take Mario Savio, the leader of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement, and his impassioned plea that his fellow students should consider the amoral machinery of corporate capitalism and the state — and then, in a kind of existential, heroic, suicidal moment throw themselves onto the “gears” of the machine in an attempt to stop it. Tom Rogers is like that. He’d never admit it, of course. Doesn’t see himself as a hero. Certainly not an existentialist or a member of Tom Hayden’s now-old New Left. But throwing himself into the path of the developer-government juggernaut is precisely what Rogers did, with pretty predictable results. Take Mario Savio, the leader of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement, and his impassioned plea that his fellow students should consider the amoral machinery of corporate capitalism and the state — and then, in a kind of existential, heroic, suicidal moment throw themselves onto the “gears” of the machine in an attempt to stop it. Tom Rogers is like that. He’d never admit it, of course. Doesn’t see himself as a hero. Certainly not an existentialist or a member of Tom Hayden’s now-old New Left. But throwing himself into the path of the developer-government juggernaut is precisely what Rogers did, with pretty predictable results.

Which bring us back to Tom Riley — who was beginning to take a leadership role on the Orange County Board of Supervisors and was up for re-election in 1978. There was only one thing for our cowboy hero, Tom Rogers, to do. He gave up the lease on his cattle ranch and prepared to challenge Riley for his seat.

Rogers leaned back in the chair in his home office and looked out the window. “I was clobbered,” he said.

Back in 1978, campaign reform was “the County’s only way out of the predicament” of overdevelopment. Developers and board members were becoming inseparable. And it didn’t matter what the politicians’ beliefs were. “They’d back a communist if they could get their development rights,” Rogers said.

Rogers’ campaign strategy was to limit the amount he and Riley could spend on their campaigns to no more than $100,000 each. “But by the time I got to Riley with the plan,” Rogers said, “he’d already spent more than $100,000.”

If the issue of his abundant campaign cash resources came up, Riley simply acted dumb. He might have said something like — “Ahh shucks, I didn’t have any idea why that developer would be calling me.”

With a barrel full of loot from the development community, Riley’s campaign seized on an emerging electoral tool: direct mail. Pictured in glossy brochures, Riley became a man of the people — a voice of reason. The flip side of Riley’s direct mail campaign portrayed Rogers as a troublemaker, someone who opposed progress and upset the delicate balance only an incumbent had the poise to maintain.

Some say that the ballot is the will of the people made apparent. But money has a great influence on will. In the end, Rogers’ effort was no match for the high-end direct-mail electioneering Riley could afford. Rogers spent around $24,000, Riley eight times that amount. The margin of Riley’s win was 70 percent to 30 percent.

___

Riley’s overwhelming victory gave the Board of Supervisors and their backers in the development community new confidence. They were now convinced that their build-out philosophy was wildly popular. If the development community wouldn’t pay for roads, they figured, voters would. In 1984, they drafted Proposition A. According to A, funding for roadways — most notably Tobacco Road — would come in the form of a one-cent sales tax hike. The expected response from the voters would be a hearty, “Aye, aye, sir.”

Rogers thought differently. “If a tax helps developers, the Board is for it,” he said. “They love to give welfare to build a road. Being a conservative, I believed that if the developers put the road in, they should have to pay for it.”

If voters rejected Rogers in 1978, they embraced his philosophy six years later. The tax was crushed on Election Day.

“The ‘Yes on A’ folks spent $1.5 million — a lot of it developer money,” Rogers said. “We spent around $80,000, and we kicked their fanny 70 percent to 30 percent.”

But Rogers now admits he and others in the slow-growth community made a terrible mistake in 1984. Since Proposition A was defeated, they figured, there would be no roads; that much turned out to be true. If there were no roads, the thinking went, there could be no development; that much turned out to be tragically, wildly wrong.

“We thought they couldn’t develop if they didn’t have the road. I mean, how stupid can you be?” he said, laughing. “You learn lessons as you go along.” And the lesson Rogers learned was that nothing could stop Tobacco Road. “The County continued to go at a breakneck pace with development without any relationship to infrastructure. It was as if nothing ever happened — what Proposition A?”

Why?

“Simple,” Rogers said. “They thought they’d make it so congested that the voters would have no choice” but to surrender and vote to tax themselves to build the road.

The defeat of Proposition A’s one-cent sales tax, however, helped create a slow-growth coalition. Liberals, conservatives, libertarians, socialists, moderates and just about every longtime OC resident congregated around the philosophy of “development with discretion.”

Hitting the streets in 1987 with a petition and pen in hand, Rogers and an army of activists qualified Measure A, the Orange County Slow Growth Initiative, for the ballot.

“Slow growth” may have been a misnomer. Measure A required that new roads accommodate traffic moving at reasonable speeds during rush hours and that congestion generated by new development on existing roads be offset by traffic improvements — and this was the key phrase — “paid for by developers.”

Whatever it was called, Measure A was an overnight hit. In early 1988, every poll indicated the slow-growth initiative would pass by a country mile. The voters of Orange County were on the brink of taking control. Tobacco Road, and the philosophy it embodied, was in danger

It was a knock on the side of the head for developers and their friends on the Orange County Board of Supervisors. If Measure A passed, developers would have to pay for the roads they needed and slow-growth politicians could rise to power. Profits would drop at Philip Morris and, as Rogers put it, “If Philip Morris goes down, so does Tom Riley.” It was a knock on the side of the head for developers and their friends on the Orange County Board of Supervisors. If Measure A passed, developers would have to pay for the roads they needed and slow-growth politicians could rise to power. Profits would drop at Philip Morris and, as Rogers put it, “If Philip Morris goes down, so does Tom Riley.”

The Board of Supervisors panicked. With slow growth in the offing, the Supes rubber-stamped entitlements to development throughout the South County. In the end, 14 agreements were approved — one for every piece of developable real estate that was still available — locking in housing-to-acre densities for 20 years. In essence, the Supervisors removed from the debate over development until the year 2008 any government body or individual who would object. And what did the citizens of Orange County gain in return? Nothing.

“The County should have at least gotten something for giving the joint away — $100 a house. We’d be wealthy today, like the developers are,” Rogers said.

As the entitlements were finalized and public outcry nearly burst the walls of the chambers, Supervisor Riley went into his see-no-evil routine again. There had been plenty of time for public comment, he said. The case was closed.

“Yeah, they had a hundred meetings,” Rogers said. “But at those hundred meetings there wasn’t one person outside of their own company who was in favor of their plan. The community was absolutely 100 percent against it every step of the way.”

Developer money poured into the effort to kill Measure A — ultimately surpassing contributions to the slow-growth campaign by 33 to 1. It was quickly put to effective use. “They had a telemarketing campaign telling you that Measure A would cost billions, raise taxes and make traffic worse” — precisely the opposite of the truth.

With money again influencing the will of the people, the initiative’s lead was cut dramatically. By Election Day, June 8, 1988, the $2 million, developer-backed campaign had worked. Managed growth was drubbed, trounced, tanned and walloped, 56 percent to 44 percent.

As developers partied — toasting their victory, their cunning, their power — Rogers shouldered responsibility for the loss. “The blame for this rests right on the leadership — me,” he told the Times the day after the election.

___

Orange County’s past had been sold, its future bought. The slow-growth movement was in shambles. The real-estate division of Philip Morris was glutted with development entitlements into the next century, and Tobacco Road was a necessity. Developers could make their millions and pass the cost of infrastructure on to us.

And they did.

• With the help of Congressman Glenn Anderson of Long Beach — whose congressional assistant, James W. Barich, happened to have been an Irvine Company employee — they created federal legislation to enable Tobacco Road to qualify for federal funds.

• With the help of state Senator John Seymour, they concocted an unheard-of incentive for private toll road investors, allowing them to collect tolls for 30 years without any responsibility for toll road maintenance. That expense would go to CalTrans, the taxpayer-funded state road agency.

• With the help of county officials, they diverted $34 million from the Aliso Viejo Mello-Roos district to build sections of Tobacco Road completely unrelated to the needs of Aliso Viejo residents.

And where did that money go? To the Mission Viejo Company — or rather Philip Morris — for its work on Tobacco Road.

Staring off into an imaginary developers’ landscape, a land where there is no right or wrong — only guile, smoke and mirrors — Riley told the Times in December 1991 that he “didn’t know” about the Mello-Roos deal. But “everything was okay” and the Philip Morris arrangement “was proper.”

___

There are hundreds of similar back streets and alleyways, even major thoroughfares, that we’ve had to bypass: the Williamson Act, which allowed developers to save on taxes by declaring land “agricultural” — even though its ultimate use was clearly residential or commercial; changing the designation of Tobacco Road from “freeway” to “corridor” to give developers leverage over its development; Philip Morris’ campaign against the anti-toll road group Committee of 7,000; the anonymous anti-toll road activists who splashed red, black or white paint across signs announcing the future path of the San Joaquin Hills toll road; the monkey wrenchers who have thrown themselves in front of (or, more recently, tied themselves to) bulldozers grading the toll road bed. We could have taken a detour and discussed Philip Morris’ role in a particularly important Laguna Beach recall election; Philip Morris’ involvement in the recall of Mission Viejo’s then-slow-growth Councilman Bob Curtis; Philip Morris’ role in suing Irvine city officials who tried to stop the road. We could, in other words, have gone on and on and on. There are hundreds of similar back streets and alleyways, even major thoroughfares, that we’ve had to bypass: the Williamson Act, which allowed developers to save on taxes by declaring land “agricultural” — even though its ultimate use was clearly residential or commercial; changing the designation of Tobacco Road from “freeway” to “corridor” to give developers leverage over its development; Philip Morris’ campaign against the anti-toll road group Committee of 7,000; the anonymous anti-toll road activists who splashed red, black or white paint across signs announcing the future path of the San Joaquin Hills toll road; the monkey wrenchers who have thrown themselves in front of (or, more recently, tied themselves to) bulldozers grading the toll road bed. We could have taken a detour and discussed Philip Morris’ role in a particularly important Laguna Beach recall election; Philip Morris’ involvement in the recall of Mission Viejo’s then-slow-growth Councilman Bob Curtis; Philip Morris’ role in suing Irvine city officials who tried to stop the road. We could, in other words, have gone on and on and on.

But you’re already overloaded. And that’s just the way the people of Orange County felt after their confrontation with a corporate giant.

“It still goes on today,” Rogers said. “The developers never quit because they’ve got billions of dollars behind them. They can go on forever. They hire the best attorneys. They hire the best advisers. And as a result, the person who works as a volunteer can’t catch up.”

These days, however, Philip Morris seems to be through with Orange County. Very soon, its last home will be built and sold.

“They picked Orange County clean,” Rogers said. “Now they just want to get out.”

Rogers’ nemesis, Tom Riley, is 83 now. He retired from the Board of Supervisors in December 1994. When he stepped down, I assume he looked at his $150 cowboy belt buckle — a gift from Philip Morris — with no sense of irony. He may look to Tobacco Road in the same way. There was a time in Orange County when the words “toll” and “road” would never have been uttered in the same sentence. Thanks to Riley, the taxpayers not only built a road they didn’t want, they’ll visit a toll plaza every time they drive it.

___

You can see the hills of what used to be Rogers’ ranch from the single acre on which he now lives. On the other side of his backyard his horse awaits dinner. Somehow, though, this week the feed hasn’t been as good as usual. So Rogers’ sense of priorities commands he leave.

Stepping into his white pickup truck, looking over his acre, waving goodbye, he’s off for some better hay. Tomorrow he will be in Northern California — 100 miles north of Sacramento, where the air is clean, the water supply is good, and the scent of pine is in the air. In his 70s now, Rogers is at an age when most folks are golfing Pelican Hills, contemplating a luxury cruise or watching television. When he returns from his trip north, Rogers said, he’ll call the Orange County Transportation Corridor Agencies. He wants to delve into a bizarre decision by County officials to “voluntarily!” — the word escapes his lips, a mix of laughter, contempt and amazement — hand over tens of millions of unasked-for dollars to developers for toll road right of way.

___

Tom Rogers is my favorite Orange County Republican. Our disagreements are invariably minor, always good-humored, overshadowed by a shared love of this place. Rogers represents a Republicanism I understand, a conservatism mistrustful of anything big, backed by human-scale ideals and a willingness to fight the very people who could have made him a powerful, longtime Orange County supervisor, a state senator or a U.S. congressman.

Unlike Rogers, the disciples of unfettered land development and progress cannot enjoy the pleasures of the past. Such pleasures — cows, hillsides and ranchers watching over them — bar the door to change in the land. Developers may not oppose the old ways, but they certainly cannot afford them. How such folk came to be known as conservatives, I’ll never know. There is, after all, nothing more radical than a bulldozer, unless it is the man who owns one. Unlike Rogers, the disciples of unfettered land development and progress cannot enjoy the pleasures of the past. Such pleasures — cows, hillsides and ranchers watching over them — bar the door to change in the land. Developers may not oppose the old ways, but they certainly cannot afford them. How such folk came to be known as conservatives, I’ll never know. There is, after all, nothing more radical than a bulldozer, unless it is the man who owns one.

— Nathan

Callahan

|