The Big Reason: Legends, Mantras, Battle Cries & Truth in Advertising

As

my grandmother Elizabeth aged, nearly all her statements became

mottoes or slogans or platitudes. “It’s a great life

if you don’t weaken,” she said right after we sang

her birthday song.

Granny was 100

and we commemorated the event with 100 candles that, by the time

she inhaled, formed a single immense flame on her cake. On that

day, her age, our enthusiasm and the physics of dentistry created

a momentous occasion.

When Elizabeth

let loose, exhaling mightily toward the 100 candles, she propelled

her upper dentures out of her mouth, over the table and onto the

floor, where they skidded across the room clanging against the

baseboard.

It is legend

in my family.

If

you can reduce a reason to live down to a simple phrase, you’ve

got yourself a motto. If you can shoot your teeth across the floor

with impeccable

timing, you become a mythological figure.

—

When

the Celts went to battle, they synchronized their war cries.

These unifying

hollers became known as “slogans.” Nowadays,  slogans

are phrases used repeatedly for promotion. The difference between

a motto and a slogan is, after all, only in the value you put

on the product. “Give me liberty or give me death” is

closer to “Just do it” than we’d like to think. slogans

are phrases used repeatedly for promotion. The difference between

a motto and a slogan is, after all, only in the value you put

on the product. “Give me liberty or give me death” is

closer to “Just do it” than we’d like to think.

The search for

the right slogan may take years, but when your own special battle

cry is heard you instinctively join in.

For

those who don’t yet have a slogan, perhaps their Celtic ancestors

screamed, “Still Looking” as they charged down grassy

slopes, arrows whizzing by. Those who refuse to have a slogan

might have had ancestors screaming,“So what.”

As

a youngster, I spent a good deal of time committing television

commercials

to memory. That was when cigarette advertisements were still on

TV. Size and length were a sales point. One popular brand kept

reminding me “It’s not how long you make it, it’s

how you make it long.” Truer, more inspirational words were

never spoken.

My competition

for TV viewing time was my mom. In her youth, she was fascinated

by Aimee Semple

McPherson — the prima Southern California evangelist

of the twenties. In that tradition, Mom watched Billy

Graham crusades and received blessing pacts from Oral

Roberts and the Abundant Life Choir.

Because

of this influence, I cut my teeth as a television cross-breed — part

consumer pagan and part broadcast evangelical Christian. I wondered

where the yellow went when I brushed my teeth with Pepsodent in

a metaphysical kind of way — and surrendered my body to the Wonder Bread

of salvation.

My

first ad campaign — or branding experience — occured

during ninth grade Social Studies where Mrs. Munroe, my teacher,

gave

the class two minutes to come up with a simply stated motivation

for living.

“What

is your life’s motto?”

Ray Snider who sat next to me answered “Have fun.” The

class nodded in agreement. I was next.

“Strive,” I

said. “Even after you fail, always try to move ahead.”

I

was a earnest young man and figured that falling short and trying

harder was

standard operating procedure for the student-teacher environment,

but on the heals of “Have fun” I had pretty much harshed

the class buzz.

My primogenitors,

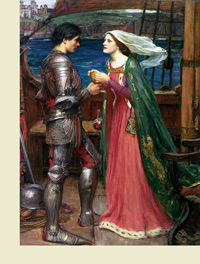

the Celts, could have helped then. The myth of Tristan

and Iseult was their gift to us — a formula for “words

to live by.”

Tristan,

the hero of this tale, spent his life in a struggle between

the “ideal” and

the “practical” — both of which were manifested

in women. Both women had the same name.

Tristan marries a “Practical” Iseult, but is emotionally and physically

driven by an “Ideal” Iseult. On his death bed he sends a secret

message across the sea to the “Ideal” with a request: If the “Ideal” still

loves him — still believes in him — she should send a ship with

white sails…if not, black sails. Tristan marries a “Practical” Iseult, but is emotionally and physically

driven by an “Ideal” Iseult. On his death bed he sends a secret

message across the sea to the “Ideal” with a request: If the “Ideal” still

loves him — still believes in him — she should send a ship with

white sails…if not, black sails.

The "Practical" Iseult,

however, learns of this secret plan. When Tristan’s dire

condition prevents him from seeing the ship arrive, he must rely

on her eyes to report. The ship appears decked in white, but when

Tristan asks, “What color are the sails?” the “Practical” replies “black.” Tristan

dies. End of story.

A

motto, then, is a light — or a sail. It is “the real thing.” It

is “true value.” It is bullshit. It is a plug; a soundbyte;

a quick fix. It manipulates us; lies to us; gives us identity.

This

is not the best of all possible worlds. This is the only possible

world — both

ideal and practical. In our gut we know it’s a great life

if we don’t weaken.

— Nathan

Callahan

|