| |

Car

Crash crucifixion: The Art of OC Register Photographer Mell Kilpatrick

The

tanker trunk is jackknifed across the 405. Don't look. Behind it

sits a totaled Pontiac, its front end crushed to the firewall, its

windshield a shroud of the driver's face. The first at the scene,

I approach the wreck on foot. The car's interior is dark; nothing

is visible at first. A Rotten.com vision

of decapitation, mangled limbs and eyeballs dangling on optical

cords makes me hesitate as

I approach the door. Frozen in anticipation, I feel the truck driver

reach over my shoulder and yank hard on the door handle. It shudders

and moans — grinding against its frame — then finally

opens to the death scene. In a procession of passing cars, the crowd

gawks

at a New Age crucifixion. It's a Mell Kilpatrick moment.

—

During

the 1950s, Kilpatrick cruised the two-lane roads of neo-natal

Orange County with his police-band radio and Speed

Graphic camera,

looking for crashes to capture on film. In the formative years

of Southern California's car culture, his beat was the aftermath

of

highway tragedy. Reflections of bent metal, dead bodies and

broken glass,

Kilpatrick's photos, like Byzantine crucifixion panels, bring

us face to face with our mortality. Tempted to turn away, we stare

with wary

fascination. His frames, frozen in time, suggest that if the crucifixion

points to the blessing of forgiveness, the crash points to the

blessing

of circumstance.

The

story of Mell Kilpatrick is about circumstance. If he were alive

today, he might say life is a series of unexpected

turns

that prove

we can never foresee how we'll be remembered.

Kilpatrick

was born in Arcola, Illinois, in 1902. An only child, he helped

with

the heavy lifting at the age of 10, when his

family moved

to Idaho in a covered wagon. They settled in the city of Windor,

where his father, James Henry, opened a slaughterhouse. Mell

wasn't prepared

for a life of meat and cleavers — at least not yet.

He married, studied coronet and dreamed of playing in a dance

band. In 1928,

determined to find a job as a musician, he moved to Southern

California with

his wife, Katherine. There, he landed a job playing the local

circuit —from

the Dianna Ballroom to the Balboa Pavilion. All the while,

he helped raise a family of five. Life was good.

Then

Kilpatrick's fortunes changed forever, re-routed by a case of

bad oral

hygiene. Flossing might have led Kilpatrick

down

a different road, but in 1947, periodontal disease prompted

the

removal of all

his teeth. It was the kiss of death for a professional horn

player. By 1948, the dentured Kilpatrick found himself commuting

from

his Santa Ana home to his new job as projectionist at the

West Coast,

Laguna and Balboa Theaters. He threaded reels of The

Big Sleep, Notorious,

The Postman Always Rings Twice, Detour and DOA. Film noir

heroes, subjects of a dark destiny, stood 20 feet tall on

the screen

as he watched. The car was a part of movie language, a symbol

of

escape, climax and danger.

The

lesson of noir wasn't lost on Kilpatrick. In late 1948, down on

his luck and with no relevant

experience, he picked

up a camera

on

a friend's suggestion and began shooting. It wasn't like

playing coronet, but photography was a paying gig.

At

first, he photographed evidence for insurance companies, then

accidents

for the Highway Patrol. They were modern-day

memento

mori—stark,

black-and-white documents of unexpected death. Hard-boiled

and methodical, Kilpatrick surveyed each wreck and pointed

his camera inside. He framed

the decapitated body. Click. He framed the twisted front

seat and the shattered skull. Click. He framed the contorted

hand reaching

like a paraplegic David through the shattered window toward

the gathered crowd outside. Click. At

first, he photographed evidence for insurance companies, then

accidents

for the Highway Patrol. They were modern-day

memento

mori—stark,

black-and-white documents of unexpected death. Hard-boiled

and methodical, Kilpatrick surveyed each wreck and pointed

his camera inside. He framed

the decapitated body. Click. He framed the twisted front

seat and the shattered skull. Click. He framed the contorted

hand reaching

like a paraplegic David through the shattered window toward

the gathered crowd outside. Click.

—

On

another road, in 400 BC, Leontius, the son of a nobleman, came

to an intersection and confronted a similar scene.

Traveling to

Athens, he noticed the corpses of crucified men.

He was curious and wanted

to rubberneck, but something held him back. There

Leontius stood, too far away to get a good look, his appetite

in conflict with

his reason — like one of us trying to see

a northbound accident from the southbound lanes.

CalTrans

calls

this the Gawk Effect.

Leontius "felt

a longing desire to see them and also an abhorrence of them," Socrates

reports in Plato's Republic. "At first,

he turned away and shut his eyes, then, suddenly

tearing them open, Leontius said, 'Take your fill,

ye wretches, of the fair sight.'"

The

same conflict haunts us when we see Kilpatrick's photos.

Confronted with the end of a life, we

want to turn away,

but instead we stare.

—

Kilpatrick

was a student of the Gawk Effect. One day, the legend goes,

he appeared unannounced

at the Santa

Ana Register with

an envelope of death scenes in his hand.

They made him a staff photographer.

Kilpatrick

worked an 80-hour week to make a living wage. On call day and

night, his

phone

number

was at the top

of every

Orange

County law enforcement and fire department

call list, including the coroner's

office.

In the darkroom, he wore a blue technician's

coat and carefully placed each negative

in an envelope

with a

title: Wreck — Chapman and

Tustin. Fatality — Grand and La

Habra. Fatality — Crystal

Cove. Wreck — Los Alamitos. Fatality — Harbor

Boulevard.

—

There's

an enormous cultural taboo around Kilpatrick's images because

death in

western culture is increasingly

private," says Mikita

Brottman, editor of the book Car

Crash Culture. A professor of liberal arts

at the Maryland Institute College of

Art, Brottman explained

how we distance ourselves from death

and isolate the dying. Every day, we

witness a cavalcade of dead bodies on

TV, she said, but in

real life, most of us are fatality virgins.

"In

our culture, bodies in their most important moments — birth,

sex, death, illness — are

not supposed to be on display," Brottman

continued. "There's something

in this ambivalence that's clarified

in Kilpatrick's photos—we

get an aesthetic pleasure looking

death

in the face, both in the 'triumphalism

of the survivor' and

in the inspiration the encounter

provides."

Brottman

recalls the character in a Gustave Flaubert

novel who feels

suicidal

and

looks into the abyss. "Somehow,

it gives him enough interest in

existence to go on living," says

Brottman. "I

think this is the kind of mesmerizing

compulsion evoked by the Kilpatrick

photographs — what Conrad

calls 'the fascination of the

abomination' — which

is, in the end, life-affirming."

I

ask Brottman to describe her

gut reaction to Kilpatrick's photos.

I wonder if

she'll say, "Take your fill,

ye wretches, of the fair sight."

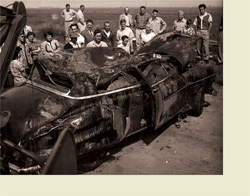

"The

Kilpatrick images are not violent or macabre to me, but peaceful

and poignant," Brottman

says. "As with crucifixion

images, there's a kind of

beatitude in the faces of

the onlookers,

as though

seeing the transcendence of

death for the first time."

—

Can

the car crash and the crucifix be seen in the

same light? Pastor

Fred

Plummer of

Irvine

United

Church of

Christ doesn't

think so.

"The

idea of the crucifixion being just a death — like a car

crash — misses

the point," he

says. "The

crucified were being

punished for an action

they took

that was an affront

to the Roman Empire.

What

Jesus did was intentional.

He died for what he

believed in.

"On

the other hand," Plummer continues, "if you race down

the 405 and crash,

the only risk you were taking is driving too fast. That's hardly

the same."

But

outside the context of social contracts — and

through the amoral

perspective of

Kilpatrick's lens — the crucifix

and the crash

form a curious parallel.

Like the crucifix,

the crash is a

vehicle of public death — an

admonition on

a road leading into town.

Like the crucifix,

the crash is a

mechanism for the death of innocence,

signaling the

rest of us to behold a

person just like

us — dressed

for work or the

bowling alley or Cub Scouts

or a bar—and

come to terms

with our mortality.

We

look at a crash

and say to ourselves, "Thank

God it wasn't

me."

Jesus

uttered a similar

prayer at

his crucifixion:

thank

God it isn't

you.

—

After

his death in 1962, Kilpatrick's

negatives

sat in his

Santa Ana darkroom

for 35

years before

falling

into the

hands of

Southern California

art dealer

and collector Jennifer Dumas.

Out of

boxes containing

more than

5,000 negatives,

Dumas

compiled

a collection

she

published

as Car

Crashes & Other Sad Stories, a 176-page coffee

table book of the dead. As Kilpatrick might have said, "We

can never

foresee how we'll be remembered." After

his death in 1962, Kilpatrick's

negatives

sat in his

Santa Ana darkroom

for 35

years before

falling

into the

hands of

Southern California

art dealer

and collector Jennifer Dumas.

Out of

boxes containing

more than

5,000 negatives,

Dumas

compiled

a collection

she

published

as Car

Crashes & Other Sad Stories, a 176-page coffee

table book of the dead. As Kilpatrick might have said, "We

can never

foresee how we'll be remembered."

"My

background is photography," Dumas says, "and especially

vernacular

photography, which is the current buzzword for accidental art or street photography —art

that was

made for some purpose

other

than aesthetic reasons."

For

whatever purpose

this

art was made,

Kilpatrick,

an

unknown

Orange

County

photographer

of the

1950s is now

a posthumous

member

of the art

scene.

He has

been

called

a "West Coast Weegee." But Weegee,

a New York news photographer

who

recorded

the seedy side of

New

York

with a Speed Graphic

camera

in the '30s and '40s,

was

much

more

in love

with

fame.

Parlaying

his

crime

scene photography into

a

career as a photographer for

Vogue,

Weegee eventually became

a

technical consultant on a number of

Hollywood

productions, including Stanley

Kubrick's

Dr. Strangelove.

Kilpatrick,

by

contrast, was

an accidental

photographer,

a

kind of real-life

film

noir hero

who

never

lived

to

see

his work

praised

by

scenesters. First,

they're

on

the front

page

of the Santa

Ana

Register. Then,

as

if in

a

pre-mortem flash

forward,

his

photographs are hanging

in

museums and

regarded as companions

to

the car-crash

silk

screens

of

Andy

Warhol.

The

pop

art

similarity

ends

there.

Kilpatrick

was

simply

doing

his

job.

Warhol

was

pursuing

celebrity

by

exploiting

the

Gawk

Effect.

Warhol's

car-crash

canvases,

like

much

of

his

work

in

the

1960s,

were

repeated

images.

His Five

Deaths

on

Orange or

Five

Deaths

Seventeen

Times

in

Black

and

White

were

composed

of

identical

car-crash

photographs

taken

on

the

streets

of

New

York

City.

The

effect

was

pop

Kilpatrick,

and

the

critics

loved

it.

"The

car's democratic banality reduces those who die in it to unidentified,

dishonored statistics, as Warhol realized," said The

London Observer's Peter Conrad about

Five Deaths on Orange.

Wrong.

Warhol wanted

our attention.

His compositions

weren't about "democratic

banality." They

were about Leontius's fair sight. Warhol

could easily have achieved the same

effect if he had decided to reproduce

Five Crucifixions Seventeen Times

in Black and White.

—

Kilpatrick's

photographs are

also cultural

companions to

J.G. Ballard's

book Crash.

Ballard created

a neo-Gothic

world in

which collision

videos replace

pornography, celebrity car crashes

are ritualized,

and sex

in and

around accident

scenes is

a kind

of underground

entertainment. Ballard,

like Warhol,

exploited Leontius's

Gawk Effect.

In Crash,

a crowd

fills the

seats at

the reenactment

of James

Dean's car-crash

death as

if it

were an

Easter Mass.

After all,

what would

a crucifixion

be without

an audience?

But Crash

is better

remembered for

mixing wrecks

and sex — maybe wrex? This auto-erotic combination

was celebrated in pop music with Daniel Miller's Crash-inspired

song Warm

Leatherette. What hip, young '80s romantic couldn't

croon, "The

hand brake penetrates your thigh — quick: let's

make love before you die"?

While

the aesthetic

of "Warm Leatherette" was the mere collision

of animal and intellectual, Ballard believed that

our world was fast becoming a victim of its own

machinery. "We

live in a world that is now entirely artificial," Ballard

said. As a result of this artifice, Crash's characters

lose touch. Their senses become cross-wired

and shorted-out. In this benumbed state, emotions

are illusory. Encounters with the face of death

are

played out in mind games, entertainment

and, yes, sex because it's one of the few other

psychological

spaces — besides

death — where

language stops.

Cyberpunk

doom aside,

though, it's

hard to

say that

we ever

speak to

the face

of death,

unless, of

course, we're

dead. So

I wonder:

Is Ballard

giving an

overdose of

technology too

much credit?

Is this

really the

reason we're

silent in

death's presence?

The answer

is in

Kilpatrick's photographs.

—

I

visited Kilpatrick's

granddaughter Carlene

Thie at

her ranch-style

home in

Mira Loma

a few

months ago.

We sat

at the

kitchen table,

ate banana

bread and

sorted through

his car-crash

negatives.

"I

sold the most gruesome ones," she said. "They

brought a bad vibe to the

house."

Kilpatrick

didn't

especially like his crash

scenes,

either. Carlene told me

he was a reluctant

photographer of car

fatalities. "It

was just a job," she

said.

On

staff at

the Register,

Kilpatrick took

tens of

thousands of

photographs — grand

openings, parades,

celebrity and official

photo opportunities

ad nauseum. His real

love was his Disneyland

photography — which

Thie self-published

in three

volumes.

But

his car-crash

photographs remain

best known.

Something unique

is expressed

in these

images — a singular

reverence made

apparent

when the audience

witnesses the vanishing

point of life.

It's an element of the

crucifixion we've

stripped away from

mainstream Christianity — the

moment when the

crowd confronts

the

tortured, lifeless

body of Jesus and

stares in silence.

Mikita Brottman

says, "The

power of the

Kilpatrick

images communicates

something beyond

language. They're

more powerful than

other images

of atrocity precisely

because of the presence

of the

observers."

These

observers exist

outside of

any cultural

framework. Within

the vacuum

of the

car-crash crucifixion,

they've lost

their social

moorings. In

Kilpatrick's

photos,

there are

no heroes

or allegiances

or patriotism

or beliefs — no

Action News

Team or God

or country

or embedded

journalist.

There's only the

space between

the observer

and death.

"What the observers are seeing is something they can never live to

talk about," Brottman says. "So

witnessing death like this has

the quality of a dream. It reveals

the frightening truth that

there are some things we can

never communicate, which raises the

question of whether we can ever really

communicate anything. As [Joseph] Conrad

said, 'We live as we dream: alone.'"

—

I

flash back to that Pontiac on the 405 whenever I leaf through

Kilpatrick's car-crash photos. There, I'm part of the crowd

that's gawking at the crucifixion. When the tanker truck

driver opens

the car door, the audience in the long line of passing cars

gawks at the Pontiac's lifeless display: a shattered femur

protrudes

through a pant leg, drops of dark maroon trickle to the

floor mat, a distorted face with scalp pulled back from its forehead — as

if blowing in the rushing wind — rests on the luminescent

dash. Here in my own Mell Kilpatrick moment, the dead have

risen from the boundaries of circumstance.

They

have risen, and the angels rejoice.

They have risen, and I am witness.

They have risen, and life is affirmed.

To them — in the gaze of Mell Kilpatrick's lens — be

glory and power forever and ever. Amen.

— Nathan Callahan,

April 17, 2003

|

|