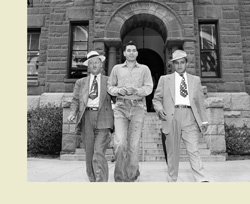

Live Noir: Stan Chambers at Henry Ford McCracken's 1952 Murder Trial

Stan Chambers, the veteran Los Angeles TV news reporter whose career at KTLA spanned more than six decades, died Friday, February 13, 2015. Chambers was the in-the-field reporter for the first live telecast of an atomic bomb test, the 1965 Watts Riots, the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, and the Tate-LaBianca murders by the Manson Family. He also broke the story on the beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles Police Department officers. One of Chamber's first TV reporting jobs was the run-up to and the trial of Henry Ford McCracken for the kidnapping of Patty Jean Hull — California's first live broadcast of a criminal case.

In

Buena Park on May 19, 1951, the parents of 10-year-old Patty Jean

Hull told police their daughter was missing. Four days

later, television cameras zoomed in on Hull's uncoiling story. As

real-time TV signals from Santa Ana's jail radiated throughout Southern

California, we entered the age of broadcast voyeurism.

Stan

Chambers, a living legend of television news, was at the mic to

bring viewers

a "first-hand picture of developments" at

California's first live broadcast of a crime case. The tease: Where

is Patty Jean Hull?

Today,

Hull looks straight at me from my computer monitor. A bitmapped

jpeg of a grammar school class photo taken

at the midpoint of the

20th century, her image is processed into a future she never saw.

It's an amplified future where TV programs starring reluctant

celebrities like Gary Condit, Elizabeth Smart, Jon-Benet Ramsey,

and O.J. Simpson

push the value of image above the value of language. But even

more, as philosopher Jean Baudrillard said in The

Ecstasy of Communication, we live in an age in which "the scene and the mirror have

given way to a screen and a network." Today,

Hull looks straight at me from my computer monitor. A bitmapped

jpeg of a grammar school class photo taken

at the midpoint of the

20th century, her image is processed into a future she never saw.

It's an amplified future where TV programs starring reluctant

celebrities like Gary Condit, Elizabeth Smart, Jon-Benet Ramsey,

and O.J. Simpson

push the value of image above the value of language. But even

more, as philosopher Jean Baudrillard said in The

Ecstasy of Communication, we live in an age in which "the scene and the mirror have

given way to a screen and a network."

If

Hull's case was tried today, CNN, Fox and Court TV might showcase

her story as an infotainment

docudrama — a "Missing Girl

Mystery." They might weigh episode tie-ins and hire ad

agencies to determine her demographic appeal.

Now,

on the 50th anniversary of her case, it's time to retell

Hull's story in the medium her tragedy helped fashion. The

only question

is what screen and what network will premiere her story of

death — and

the birth of reality TV?

"It's

in a rough stage now," I say, describing my Patty Jean Hull

docudrama to Nancy Meyer, a development executive at Universal

Studios. "But

here's what I see."

It

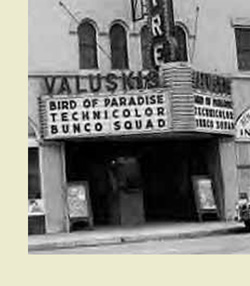

is midday on May 19, 1951. A hard light flares off the marquee

at the Buena Park Valuskis

Theater. In the distance,

a man in

a green gabardine sport suit approaches. A few cars scroll

past on

Beach Boulevard

in this agricultural community of citrus growers. Suddenly,

Patty Jean Hull's face pops into full frame. A 10-year-old

in pigtails,

a red sweater, blue jeans, bobby socks, and saddle shoes,

she smiles, turns, takes the hands of her two younger

brothers and

walks to

the ticket window for the matinee. It

is midday on May 19, 1951. A hard light flares off the marquee

at the Buena Park Valuskis

Theater. In the distance,

a man in

a green gabardine sport suit approaches. A few cars scroll

past on

Beach Boulevard

in this agricultural community of citrus growers. Suddenly,

Patty Jean Hull's face pops into full frame. A 10-year-old

in pigtails,

a red sweater, blue jeans, bobby socks, and saddle shoes,

she smiles, turns, takes the hands of her two younger

brothers and

walks to

the ticket window for the matinee.

Meyer listens intently as I continue.

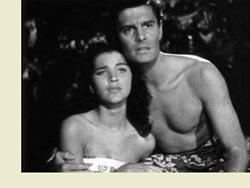

Theater

interior. The

Bird of Paradise, a motion picture playing that

day,

fills the screen. Tiki Room music and

Technicolor

palm trees

set the scene, as André, a white man who has

sailed to Polynesia, is about to marry Kalua, an island

princess.

We zoom in on the screen

as Kalua's brother Tenga explains a native honeymoon

night to André:

TENGA:

You will kidnap Kalua. It would bring great shame to the chief

if he let her

go easily. She must be taken

from

him by force.

ANDRÉ:

But I don't need to take Kalua by force. She wants to come with

me. She loves

me.

TENGA:

That is true, but when you kidnap her, she will fight you and

bite you. That is the custom.

It proves

that she

loves her

parents. It proves that she does not willingly

run from their happy house.

At

the Valuskis Theater, Patty Jean Hull is seated alone, away from

her brothers and the crowd. Someone

approaches.

It's the

man in

the green gabardine sport suit: Henry Ford McCracken.

He sits down immediately

next to her.

"I'm a little lost now," Meyer says. "Who

is McCracken?"

"McCracken

was 34," I say, "a handyman and country musician.

Slicked-back hair, clean-shaven, inconspicuous-looking.

He never touched alcohol. In fact, he wouldn't drink Coke at a bar for fear

it was

spiked."

McCracken

was also a sexual psychopath on a short fuse. In 1946, his concerned

mother

petitioned

the Orange

County Superior

Court

to have

him committed to a mental hospital. His

behavior and record as a serial child sex offender,

however, failed

to impress

medical examiners

who

said he had "mild schizophrenia with

anxiety neurosis but can distinguish between

right and wrong." Diagnosis: no big deal.

"What

else can you tell me about McCracken?" Meyer asks.

After

his "mild

schizophrenia" diagnosis, McCracken moved

from Orange County to Michigan, where

his string of child sex offenses continued. In the fall of 1950,

after nine arrests, Detroit Police

prepared documents to have him permanently

committed to a mental institution. Before the documents were filed,

McCracken fled back to Orange County.

A few weeks later, he was arrested in

Santa Ana for failing to register as a sex offender. He served

a six-month jail sentence. On May 6,

1951, he was on the streets again.

McCracken immediately gravitated to

an auto court cottage down the block

from

the Valuskis

Theater

where he took

up residence.

He worked

nights entertaining at the nearby White

Elephant Cafe. Just 12 days after his

release from

the Santa Ana

Jail, he took

an empty

seat

at a Saturday matinee, next to Patty

Jean Hull. McCracken immediately gravitated to

an auto court cottage down the block

from

the Valuskis

Theater

where he took

up residence.

He worked

nights entertaining at the nearby White

Elephant Cafe. Just 12 days after his

release from

the Santa Ana

Jail, he took

an empty

seat

at a Saturday matinee, next to Patty

Jean Hull.

Meyer

shifts in her seat. "We'd

have to look delicately at a child

sex-offense case like this," she says

"I

can go that way," I say. "Let's

fast forward."

Hull

never returned home from the theater. Her parents

called the

police that night. By

the next morning, nearly every

family in Buena

Park, a community of 5,000,

sent someone out to look for the missing girl.

That

afternoon, on a tip from the owner of the White Elephant Cafe,

police took

Henry Ford

McCracken into custody. He

went quietly. A bloodstained

green gabardine sport suit was found

in his cabin.

Outside

the jail, one of the most exhaustive searches in

Southern

California history

continued. More

than 1,500 people,

including

Boy Scout troops and Marines

from El Toro, scoured hillsides,

orange

groves

and back yards for Hull. They

searched for days with no

luck.

"Now, for the electronic moment of truth," I say to Meyer. "On

Wednesday, May 23, camera

crews arrived on the scene to provide Southern California's television

audience its first exposure to a live crime

drama. After the Hull case,

TV would never be the same."

"I

think if I were to develop this," Meyer says, "I'd say

the murder sounds — I

don't mean this the wrong

way — but

almost incidental."

"But

as history," I say, "I think this story would

be a great lead-in to a live crime series.

Let me just wrap up the pre-trial."

It

is Thursday, May 24, 1951. Our view pans across Live

Oak Canyon. A State

Forest Ranger

crawls

under a barbed-wire

fence

and moves

toward a tiny mound

of dirt marked by a broken branch. The ranger

drops to

his knees and begins

digging with his hands. He stops. Hesitates.

Digs down

deeper. We

zoom in.

We see a

black-and-white saddle

shoe breaking through

the loose dirt that covers this shallow

grave. It

is Thursday, May 24, 1951. Our view pans across Live

Oak Canyon. A State

Forest Ranger

crawls

under a barbed-wire

fence

and moves

toward a tiny mound

of dirt marked by a broken branch. The ranger

drops to

his knees and begins

digging with his hands. He stops. Hesitates.

Digs down

deeper. We

zoom in.

We see a

black-and-white saddle

shoe breaking through

the loose dirt that covers this shallow

grave.

"This

is this all true?" Meyer asks. I nod.

The

camera tilts up and lingers for a moment, registering the emotion

of the

ranger and the grave. The shot dissolves into

the same scene

a few hours later

as police detectives surround Patty Jean's body.

She is

fully

clothed, face up, hands folded across

her stomach.

Back

at the Santa Ana Jail, McCracken

is taken

out of

his cell. Police

wait outside

to transport

him

to the

grave

site. As he

walks down

a corridor in

front of cameras,

District

Attorney

James

L. Davis holds

out a bloodstained

yellow

bed sheet found

near

Patty Jean's

body.

He asks McCracken, "Is

this yours?" There

is no reply.

"This

might be something that Court TV would consider," Meyer

says. "What

happened next?"

I

relate McCracken's

version

of events. He

admitted

to police

that Hull

visited

his cottage

but

said she

panicked when

she thought

her neighbors

were

approaching.

Embarrassed

and

trying

to evade

them,

she attempted

to escape

out a screen

window,

slipped and accidentally

cut herself.

According

to McCracken,

she

passed out.

After

he attempted

to revive

her, he

claims he,

too,

passed out.

Meanwhile,

the autopsy

report

had been

completed.

It documented "small

bruises

on the

girl's

arms and

on the

area of

her thighs,

dilation

of her

rectal

orifice,

some 15

gashes

on her

scalp

at the

back and

sides,

and three

fractures

of her

skull."

The

TV cameras

surrounding

the

murder were beginning

to

have

their

effect.

Before

the

Aug. 3 trial,

McCracken

attorney

George

Chula

Jr.

filed a change

of venue

request

based,

in part,

on the

claim

that

live

coverage had "aroused

the

anger and indignation

of the

people." Request

denied. The

TV cameras

surrounding

the

murder were beginning

to

have

their

effect.

Before

the

Aug. 3 trial,

McCracken

attorney

George

Chula

Jr.

filed a change

of venue

request

based,

in part,

on the

claim

that

live

coverage had "aroused

the

anger and indignation

of the

people." Request

denied.

Drawing

media

coverage

across

the

country,

the

first

trial

ended

with

a

deadlocked jury.

McCracken

was

found

guilty

of

child stealing,

but

one

juror

dissented

on

the murder

charge.

As

Superior

Court

Judge

Robert

Gardner

dismissed

the

jury,

McCracken

reacted

like

a

child. "I

knew

I wasn't

guilty," he

chanted

over

and

over

again

in court.

As

the

jurors

walked

down

the

stairs

from

the

third-floor

courtroom,

they

hid

their

faces.

A

reporter on the

stairway

landing

lunged

forward

with

his

camera.

A

male juror

shoved

back,

smashing

the

camera

into

the

reporter's

eye.

As

he

stumbled

backward

with

blood

running

down

his

face,

the

reporter

caught

the

juror

with

a

left hook to

the

jaw.

A

brawl followed

between

jurors

and

newsmen.

A

sheriff's deputy

intervened.

There

was outrage

everywhere in

Southern California.

Orange County

citizens organized

rallies to

protest the

verdict. District

Attorney Davis

was so

angered by

the outcome

that he

berated the

jury for

failing to

convict.

Trial

No. 2

was set

to begin

on Aug.

13.

"So

what was the final outcome?" Meyer asks.

I

tell her that the prosecution at the second trial was

meticulous. The jury was bussed to McCracken's cottage.

This time, there was no mistrial.

McCracken

was found guilty of first-degree

murder. I

tell her that the prosecution at the second trial was

meticulous. The jury was bussed to McCracken's cottage.

This time, there was no mistrial.

McCracken

was found guilty of first-degree

murder.

On

Feb. 19, 1954, after a three-year battle to escape the

gas chamber, McCracken was executed.

I

wait for Meyer's response. "I see murder stories all the time," she

says. "I think the real story

here is how this changed the community and the way people look

at murder.

Have we lost our innocence?"

"That's

exactly how I would focus the story," I explain. "This

is about the birth of crime and reality TV. Cops, Investigative

Reports, The

People's Court — all owe

a debt to the Hull case. Think two words: 'live noir.'"

"Well,

then," Meyer says. "I'll give my friend

at Court

TV a call. It might be something they'd be interested in."

The

meeting is over.

I drive

to North

Hollywood

and bolt down a

cup of

coffee — reassuring

myself

that I can live

with Court

TV. Now,

I just have

to figure

out if

we've

lost our

innocence.

According

to most

late-20th-century

cultural

historians,

the

official

date

of America's "innocence

lost" is

Nov.

22,

1963 — the

day

of

JFK's

assassination.

The

payoff

for

fans

of early

live

crime

coverage

came

two

days

later

on

Nov.

24,

when Jack

Ruby

shot

Lee

Harvey

Oswald dead

before

a live

TV audience.

Like

a NASCAR

race

car

hitting

the

wall

on ESPN,

Ruby's

act

of

expedient

justice

was

the

spectators'

defining

moment

in vicarious

danger.

With

those

same

visceral

and

yet

unrealized

expectations

in

mind,

any

Southern

Californian

who

owned

a TV

in

1951

witnessed

the

spectacle

of

McCracken "live." How

did

this

affect

the

audience?

What

innocence

were

we

presumably

losing?

It

occurs

to

me

that

the

best

point

of

view

for

my

Hull

tele-tragedy

might

be

found

through

the

eyes

of

someone

on

the

scene.

"This was a groundbreaking event in television news," Stan

Chambers

tells me. Chambers, KTLA-TV's on-the-scene reporter, has covered most

of the major events in Southern California over the past 50 years, including

the Hull case. "This was a groundbreaking event in television news," Stan

Chambers

tells me. Chambers, KTLA-TV's on-the-scene reporter, has covered most

of the major events in Southern California over the past 50 years, including

the Hull case.

"You

really have to give credit to station manager Klaus Landsberg," Chambers

says. "His philosophy was to

get the cameras out of the studio and into the field. It all

fell

together on the Patty Jean Hull case. It was his idea to cover

it."

So

it's Landsberg

who lost

our innocence,

I think.

"When the word came out that they were holding McCracken," Chambers

says, "we went over to his

house. Our cameras looked through his front window and

saw all this

pornographic material."

Pornography

broadcast

live

in 1951

to all

of Southern

California?

That's

another

first.

I ask

Chambers

to

describe

it.

"It was mainly magazines," he says. "There wasn't

that much pornography around, so it's hard to be relative

about it."

When

news of

McCracken's whereabouts

got out

via live

TV, a

crowd of

angry locals

gathered

at the

Santa

Ana Jail. "We were there

live," Chambers says. "It

was almost what you would call a lynch mob. There

were some very

nervous moments."

Later,

during

the

trial,

KTLA

had cameras

in the

hallway

outside

the courtroom. "When people

would come in and out of the courtroom

door," Chambers says, "our

cameras would get a peek as to

what was going on.

Then,

when witnesses

finished their testimonies,

we would do interviews. There were

little games being played."

The

Hull

case

also

marked

the first

time

in

California

history

that

newspaper

and TV

reporters

competed

for a

crime

story.

"Once, someone mysteriously knocked the power line out of the wall

so our cameras went off the air. We were looking around wondering where our

signal went. It was chaos."

Then

I ask Chambers the magic question: "Do

you think we lost

a part of our innocence

as a result of our

exposure

to the Hull case?"

"The audience has changed a lot," he says. "In

those days, there was such a thing as real shock. Nothing

like this had happened

to us as broadcasters before, and it hadn't happened to

the people we were interviewing — or the

audience either.

"The scope of news was broadened by events like this," Chambers

says. "News became very much

more visual and began to have a much stronger impact

on people.

You were there right as it was happening. It was reality."

There's "reality," and

then there's "reality."

The

instant

communication

of television

removed

the

wall

between

crime

and

public

reaction.

We saw

Patty

Jean

Hull's mother

covering

her

own face

from

the

camera's

unblinking,

shameless

gaze.

We saw

her listless

brother

crying.

We saw

her father pleading

for

justice.

According

to Baudrillard, "It

is futile to imagine space if

one

can cross it in an instant. Picturing

others and everything that brings

you close to them is futile from

the instant that 'communication'

can make their presence immediate."

With

the advent

of live

crime

TV,

an immediate

presence

confronted

us.

We

could

instantly

see ourselves

in a

victim's

circumstances.

We could

imagine

what

we would

do. We

could

judge

their

reaction. But as

viewers — as voyeurs — the

current flows only one way. We

could take in the victims' first-hand

reactions — to

place, time and circumstance.

But

we could not touch the scene

through

the airwaves.

"In the McCracken case, you've got the ingredients for making

people watch: molestation, sex and a guy who's a sexual

psychopath," Clay

Calvert says.

Calvert

is the

author

of Voyeur

Nation,

a study

of the

cultural

phenomenon

of media-driven

voyeurism.

He

seemed

the

most

likely

candidate

to

help

me

determine

if we've

lost

our innocence

since

this

first

electronic

moment

of

truth. "When we watch things

like the McCracken case on television, we are removed

from actually dealing

with those people. We dip in and out of their lives.

We turn off the TV set, and our responsibility is nil.

We're feeding

off their tragedy and grief."

"Yes, but haven't we always had an interest in other people's misery?" I

ask without shame.

"Mass

voyeurism has been around at least since 1836, when the New York

Herald covered the ax murder of a prostitute," says Calvert,

an assistant professor of communications and law at Penn State. "But

the McCracken case helped to break the mold. It was live.

For the audience,

it was the first time that the outcome was unclear. There

was drama, suspense, it was unscripted — we

didn't know what to expect."

"How is that different than what we see on TV today?" I

ask.

"Since

then, it's been a case of constantly pushing the envelope. Each

generation's audience seems more willing to see more of other

people's private

lives — more willing

to tolerate certain uses of cameras than previous generations were."

"Have we lost our innocence?" I ask.

"We

gaze at our new reality, feeling involved when we may not be," Calvert

says. "With an increasing amount

of TV reality shows, fact and fiction, acting and being are

getting harder

to distinguish."

The

scene

shifts.

It is

1951,

and

we are

once

again

inside

a

theater

at

the screening

of The

Bird

of

Paradise.

TENGA:

As soon

as you

kidnap

her,

the

big

drum

will

sound

the

alarm.

My

father

will

rush

out

in anger

because

someone has

stolen

his

daughter.

And

I

will

rush

out

with

my weapons,

and

all

our

warriors

will

come

with

their

weapons,

and we will

look

for

you.

We

will

look

everywhere.

ANDRÉ:

Where will I be?

TENGA:

You

will

have

carried

Kalua

into

your

house.

ANDRÉ:

But that's the first

place anybody would look.

TENGA:

Yes.

But

we will

not find

you.

That

is the

custom,

too.

Did

McCracken

find

it increasingly

difficult

between "acting" and "being"?

Did he imagine Patty Jean to be

Debra Paget, who played Kalua in

The Bird of Paradise? Was his kidnapping

of Hull part of some movie-based

delusion? Are we guilty, today,

of sharing a similar part of McCracken's

delusion? Did

McCracken

find

it increasingly

difficult

between "acting" and "being"?

Did he imagine Patty Jean to be

Debra Paget, who played Kalua in

The Bird of Paradise? Was his kidnapping

of Hull part of some movie-based

delusion? Are we guilty, today,

of sharing a similar part of McCracken's

delusion?

I

turn

on

the TV

and surf

through

the

channels.

There's

Judge

Judy

providing

us

with

a

21st

century

pillory.

There's

the parents of Danielle

van Dam,

the once-missing

seven-year-old

San

Diego

girl

whose

body

was found

by a

roadside.

There's

Daniel V.

Jones,

the

Los Angeles

man who

on May

1, 1998,

pulled

his

truck

to

the side

of an

offramp,

set

it on

fire

and

then

shot himself

in

the head

with

a

rifle

on

live

TV.

There's

Law & Order and Fact or Fiction and Law & Order:

Special Victims Unit. There's

Elizabeth

Smart playing the harp and the

skull of Chandra Levy.

When

I get

the call

from

Nancy

Meyer

at

Universal

Studios,

I'm taken

off-guard.

She

goes

straight

to the

point

I

talked to my friend at Court TV," Meyer says. "Unfortunately,

because there are more alarming and lurid cases that have

come

along, your story is not the kind of thing — as she understands

the marketplace — that

she would want to incorporate into programming."

"Incorporate into programming" echoes like a dub remix

in my head.

"That doesn't mean this is the end of it," she offers. "Everyone

has a nose and an opinion. Someone else may have an interest

in this."

Today,

a hard

light flares

off the

cars at

Ken Grody

Ford in

Buena Park.

This is

where

the Valuskis

Theater once

stood. After

Patty

Jean's

kidnapping, customers

stayed away,

business declined

and the

place shut down.

By the

1960s, the Valuskis had become

a Pussycat

Theater. Now

it's a

car lot.

The

Hull

family home

has been

torn down,

too — so

has the White Elephant Cafe. A little farther down Beach

Boulevard, a

law office occupies the lot where McCracken's cottage

once stood.

Santa Ana's Courthouse still stands at the corner of

Broadway and Santa

Ana Boulevard, but now it's a museum. If you want, you

can sit

in a juror's chair or walk down the hallways where TV

cameras made

history. Today,

a hard

light flares

off the

cars at

Ken Grody

Ford in

Buena Park.

This is

where

the Valuskis

Theater once

stood. After

Patty

Jean's

kidnapping, customers

stayed away,

business declined

and the

place shut down.

By the

1960s, the Valuskis had become

a Pussycat

Theater. Now

it's a

car lot.

The

Hull

family home

has been

torn down,

too — so

has the White Elephant Cafe. A little farther down Beach

Boulevard, a

law office occupies the lot where McCracken's cottage

once stood.

Santa Ana's Courthouse still stands at the corner of

Broadway and Santa

Ana Boulevard, but now it's a museum. If you want, you

can sit

in a juror's chair or walk down the hallways where TV

cameras made

history.

When

I visit

these

places,

Baudrillard's

observation

of the

futility

of

imagining

space

when

distance

can be

diminished by

time

settles

hard

in

my consciousness.

I wonder

how far

we've

actually

come

in

so short

a time

and how

much,

if

any,

innocence

we have lost.

This

July

22,

50 years

will

have

passed

since

the

Supreme

Court

of

California

ruled

on Henry

Ford

McCracken's

appeal. That

ruling

set

another

precedent.

It was

the

first

appeal

in

California

history

in which

live

television

coverage of

a crime

case

was

considered

in

the

determination

of a

fair

and

impartial

trial.

In response

to the

inauguration

of the

electronic

moment

of

truth,

the

appeal

failed.

Since

then,

we

tell

ourselves

that

everything

has

changed.

Because

of

television's

prying

eyes,

we

believe

that our

TV

reality,

as

Baudrillard

wrote

more

than

20 years

ago, "is no longer a

question of imitation, nor duplication,

nor even parody. It is a question

of substituting the signs of the

real for the real."

Yet,

there

has

always

been

a fascination

with

crime

and its

consequences.

In

the past,

we turned

it into

folklore

and

staged it

in theaters.

Since

the

first

cave

drawings,

we

visualized

ourselves

in a

victim's

circumstances

from

a

distance.

We

have

always been

voyeurs,

only

now

we have

another

buffer

zone — our television screen — between "the

signs of the real and the real."

In

the

presence

of projected

images

of

crime

and

its

consequences — and

other people's grief — we

may feel guilty, but we still

watch.

Live or not, the future and

the past coalesce in little

more than

a retinal response. In the

end, Patty Jean Hull stares

out from

this page, and we stare back.

— Nathan Callahan,

July 18, 2002

|